Explore Feuilletons

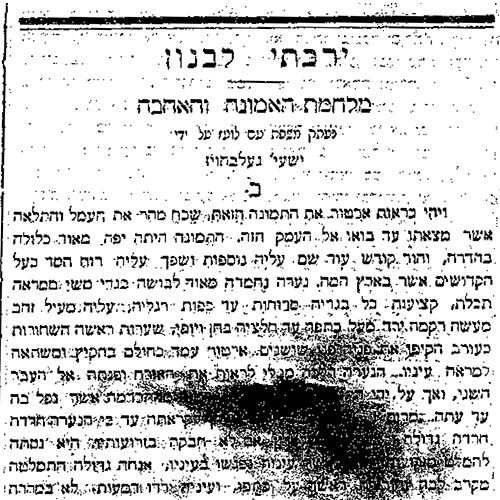

The War of Faith and Love

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Related Text

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Grace Aguilar, Yeshay(ahu) Gelbhaus (translator), “The War of Faith and Love,” 1874. Translated by Marina Mayorski

Chapter 2

When Arthur saw this vision, he quickly forgot the travails and hardships he had gone through before his arrival in this valley.

Read Full

The vision was very beautiful, perfect in its splendor, and a holy glory imbued it with graceful spirit as on the holy ones in the land.1 A lovely young woman was wearing a blue silk dress that reached her feet, all her garments fragrant with cassia2, a golden embroidered coat descending gracefully from her shoulders to her hips. Her hair, dark as a raven, surrounded her face, a face of roses. Arthur stood there, as though in a daydream, marveling at the sight before him. The girl turned to leave without seeing the guest […]3 only then was he roused from the drowse he had slipped into […] suddenly moving towards her and startling her such that she would have fallen to the ground had he not caught her in his arms. She attempted to flee his embrace […] when her eyes met his and a great sigh escaped from the bottom of her soul as she lowered her head to his shoulder and tears streamed down her face. It took a long time before the lovers separated from each other. Arthur reminded Miriam of those early days, how he had mended his ways to seek her love, and how happy he had been when Miriam confessed with her own lips that she loved him. He bemoaned the cruel fate that had kept them apart for so long. Miriam listened but did not reply, either good or evil4, and Arthur said:

“At this very moment, I shall surely remember those last words that I heard from your lips before I left, words that were a riddle to me, and I remember the effect they had on me: lest my heart be sound and secure in your love for me, for it would be a crime for you to love me.”

“My words were truthful,” Miriam replied, “in the gale of my emotions I had forgotten that we are both ripe for stumbling if we continue down the path of this love.”5

Hearing these words, Arthur implored Miriam to elucidate their meaning, for they were as cryptic as a sealed book to him.6 When they last had spoken, fifteen months earlier, the king had ordered Arthur to hurry and join the army gathering under his flag in preparation for battle with the enemy, and Arthur had hastened to carry out the king’s command and had departed with Spain’s legions to the clash of arms.7 Upon his return from the battlefield, Miriam had disappeared, and Arthur did not know what had happened to her. Don Alberto, in whose home Miriam had stayed for a long time, said that she had returned to her father’s home, but he was not inclined to disclose its location. All of Arthur’s efforts to find it had been in vain8, and he did not understand what was this and for what was this.9 Why was he prevented from inquiring about her father’s whereabouts, to request and plead with him for his daughter’s hand in marriage?

Arthur’s heart groaned as he beseeched Miriam to explain her words, his voice hewing flames of fire.10 But Miriam begged him to leave her at once and forget that forsaken valley,11 for her life and the life of her father were in danger if anyone found out about this place.12

“A secret is concealed here,” Arthur thought. Miriam’s tumult would not abate until Arthur swore that he would never divulge where his legs had taken him that night. But what was the awful thing that could not see the light of day? Why did Miriam consider it to be such a terrible sin to love him? Time and again he pled with her to tell him, but she was steadfast in her refusal.13 His soul was faint,14 his ideas dwindled, and doubt pestered him.

“Were you betrothed to another man?” he asked woefully.

“That’s not the case, Arthur. I will not wed another, nor is there a man that would ask that of me. Oh, my heart, my heart!”

“Then why would you consider your pure love to be a sin? Why would you send me away if no man stands between us?”

“Though no ‘man’ stands between us, God will still forbid our love. My father’s curse will stand between us. Tempt me no more, leave me to my cruel fate, entreat me no more with your amicable words that puncture the deepest chambers of my heart like the stab of a sword.15 Oh, woe, why? Why have you loved me?”

But Arthur did not acquiesce to her pleas and urged her to disclose the secret concealed within her, because he thought he would be able to remove any obstacles if he could only see them. Miriam listened a bit more and then turned her face from him. Suddenly she saw that his knees had buckled and his face had paled.

“So be it,” Miriam exclaimed, “I will show you the great wall that stands between me and you. I withheld this not because I feared you would tell anyone of our whereabouts, that never entered my mind, but because I feared your disdain and abhorrence.”

“Disdain and abhorrence? Are you mad?”

“If you do not believe me, listen and you shall see” – her face turned sickly green as she spoke,16 but her being advanced with valor,17 and she vehemently cried out: “I am a daughter of Judah!”

Once Miriam’s lips uttered the words, Arthur retreated. He let go of her hand, which had been tightly enclosed in his, and his face displayed signs of scorn and love mingled together as his whole body swayed as the reed sways in water.18

“Now you surely know everything, and now it is needless to say,19 go, leave me once again,” Miriam added, “forgive me for having deceived you thus far and forget me from now on, remember what I am, and you will soon cease loving me.”

“Never, never!” Arthur cried out, and, unwittingly, he kneeled before Miriam: “Go forth with me to my land, to my birthplace, there no one will know who you are and where you came from.20 For what matters your race and the rock from which you were hewn to me,21 my soul is bound in yours and I will never stop loving you for as long as I live, go forth with me. King Edward sent for me once again, he promised to return me to my bedrock and my estate and I have not heeded, but for you, Miriam, I will forget all the anguish he caused me and will accede to his burdensome yoke.22 Be mine, and we will spend our days on earth in bliss.”

“And what will become of my father?” – the girl asked woefully – “will you be willing to take him under your wing as well and be a son to him?”

Arthur looked away, moaned and remained silent.

“Surely, this you cannot do? I knew as much. I am grateful for your sublime love. I cannot be a wife to you.”

“And yet you carry love’s name on your lips?” Arthur replied and rose like a lion wounded by an arrow23, realizing that his hope has been dashed.24 “I would be willing to leave Spain for you, leave the generous king who has bestowed kindness on me; willing to go and work under oppression,25 all just for you, to find a home for you. I would not heed all the judgments of the world; I wish to mingle the pure blood of Stanley with the muddied fountain that gushes in your veins;26 I would forget your family name, your people, but not you. But how do you repay me? You reject me out of hand, send me away, and yet your lips speak of ‘love.’ Lies are coming from your mouth, your soul yearns for another!”

“Indeed, your words are honest and your judgment is just,27 you reminded me of what I have almost forgotten in my turmoil, that there exists a love that is even more powerful than the love I have for you. I may forget everything, but I cannot forget my God, the God of my forefathers!”

These words sunk to the bottom chambers of Arthur’s heart28 and robbed him of his hopes and dreams. Confused, he paced back and forth, and calm was beyond him. The terrible, sudden disaster had caught him off-guard. When he had taken leave of Miriam fifteen months earlier, he had been willing to give his life for her. Since that day, Miriam’s only prayer was that he would forget her and that she and her memory would vanish from his heart. But, to her great dismay, this was not to be. She believed herself to be strong enough to combat love, but in one glance Arthur had rekindled it, in one word he exposed her frailty.

“I will do as you say,” said Stanley, “and leave you now but not forever. If you truly and wholeheartedly love me, time will not change your love. One day you will be lonely and alone in the world, as a shrub in the desert,29 and I will be your protector and you will be mine, despite your tribe and your people.

“Do not hope for this, Arthur, it is better if you hate me as your people hates mine. I can hardly bear your pleasant words, I cannot hold them.30

The girl’s voice faded but her lips motioned inaudibly as she fell into the British man’s arms, and tears streamed down her cheeks like a current of mighty gushing waters,31 but she soon came to her senses and eluded Arthur’s loving embrace.

“But this is folly,” Miriam cried out, “folly and absurdity! Do not go there!” – she added, when she noticed that he planned to go towards the hill – “there is a better way, follow me. I hope you will not betray what you’ve seen here?”

“Nothing!” Arthur replied.

Miriam went first and he followed her on a desolate path, until they came to a tall stone wall, where Miriam lifted tangled brushwood and a door opened, revealing a shaft with a staircase. Now, too, Miriam went ahead of him as dim light shone on the crooked slope from the cliff’s grottos and the rock’s crevices. And once again a staggering wall stood before them. Another door opened by itself and closed behind them once they passed through it. With immense efforts they made their way between thorny bushes that sprawled like a fence before any watchful eye, and suddenly Miriam rose and stood up. Stanley looked around with horror as he saw an endless plain spread out as far as the eye can see. The plain was brimming with white rocks, strewn all over in disarray. The stone wall that had opened for them just moments ago had vanished from sight. Arthur looked back, in vain, to see where he came from.

“This road is dreadful, but it is not as bad as it seems. Turn right, and that path will lead you safely to a guesthouse. Tomorrow when the sun rises you will see a small town on the border and from there you will be on your way. The night is swiftly covering the sun with a shroud of darkness, so you must not linger here, Arthur.”

And yet Arthur did not budge, until Miriam confessed her heartfelt love for him once again and swore that she would never give her affection to another. And so they parted. Shortly thereafter, no human form could be seen on the plain.

(to be continued)

- Originally: ״כעל הקדושים אשר בארץ המה״. See Psalms 16:3: “As to holy ones in the land and the mighty who were all my desire” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״לִקְדוֹשִׁים, אֲשֶׁר-בָּאָרֶץ הֵמָּה״ ↩

- Originally: ״קציעות כל בגדיה סרוחות עד כפות רגליה״. See Psalms 45:9: “Myrrh and aloes and cassia all your garments. From ivory palaces lutes gladdened you.” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״ מֹר-וַאֲהָלוֹת קְצִיעוֹת, כָּל-בִּגְדֹתֶיךָ; מִן-הֵיכְלֵי שֵׁן, מִנִּי שִׂמְּחוּךָ״. ↩

- A dark mark on the page of the newspaper makes this section and the ellipses that follow illegible. ↩

- Originally: ״מרים שמעה כל זאת ולא ענתה דבר למטוב ועד רע״. See Genesis 41:24: “And God came to Laban the Aramean in a night-dream and said to him, “Watch yourself, lest you speak to Jacob either good or evil!” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); “וַיָּבֹא אֱלֹהִים אֶל לָבָן הָאֲרַמִּי בַּחֲלֹם הַלָּיְלָה וַיֹּאמֶר לוֹ הִשָּׁמֶר לְךָ פֶּן תְּדַבֵּר עִם יַעֲקֹב מִטּוֹב עַד רָע” ↩

- Originally: “לצלע שנינו נכונים”. See Psalms 38:18: “For I am ripe for stumbling and my pain is before me always” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); “כִּי-אֲנִי, לְצֶלַע נָכוֹן; וּמַכְאוֹבִי נֶגְדִּי תָמִיד” ↩

- Originally: “אשר כדברי ספר החתום המה לו”. See Isaiah 29:11: “And the vision of all things shall become to you like the words of a sealed book that is given to one who can read, saying, “Pray, read this,” and he says, “I cannot, for it is sealed” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וַתְּהִי לָכֶם חָזוּת הַכֹּל, כְּדִבְרֵי הַסֵּפֶר הֶחָתוּם, אֲשֶׁר-יִתְּנוּ אֹתוֹ אֶל-יוֹדֵעַ הספר לֵאמֹר, קְרָא נָא-זֶה; וְאָמַר לֹא אוּכַל, כִּי חָתוּם הוּא״ ↩

- Originally: ”ויצא בין צבאות ספרד לקראת נשק”. See Job 39:21: “He churns up the valley exulting, in power goes out to the clash of arms.” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״יַחְפְּרוּ בָעֵמֶק, וְיָשִׂישׂ בְּכֹחַ; יֵצֵא, לִקְרַאת-נָשֶׁק״ ↩

- Originally: ״כל יגיעות ארטור לגלות ולמצוא אותו נשארו מעל״. See Job 21:34: “And how do you console me with mere breath, when your answers are naught but betrayal?” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וְאֵיךְ, תְּנַחֲמוּנִי הָבֶל; וּתְשׁוּבֹתֵיכֶם, נִשְׁאַר-מָעַל״ ↩

- Originally: .״ולא ידע ארטור מה זה ועל מה זה״ see Esther 4:5:“And Esther called to Hatach, of the king’s eunuchs whom he had stationed before her, and she charged him concerning Mordecai to find out what was this and for what was this” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וַתִּקְרָא אֶסְתֵּר לַהֲתָךְ מִסָּרִיסֵי הַמֶּלֶךְ, אֲשֶׁר הֶעֱמִיד לְפָנֶיהָ, וַתְּצַוֵּהוּ, עַל-מָרְדֳּכָי--לָדַעַת מַה-זֶּה, וְעַל-מַה-זֶּה״ ↩

- Originally: ״וקולו חוצב להבות אש״. See Psalms 29:7: “The LORD’s voice hews flames of fire” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); “קוֹל-יְהוָה חֹצֵב לַהֲבוֹת אֵשׁ” ↩

- Originally: .״הנשכח מני רגל״See Job 28:4: “He breaks under a stream without dwellers, forgotten by any foot, remote and devoid of men” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״פָּרַץ נַחַל מֵעִם גָּר הַנִּשְׁכָּחִים מִנִּי רָגֶל דַּלּוּ מֵאֱנוֹשׁ נָעוּ״ ↩

- Originally: ״חייה וחיי אביה תלואים מנגד״. See Deuteronomy 28:66: “And your life will dangle before you, and you will be afraid night and day and will have no faith in your life” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); וְהָיוּ חַיֶּיךָ, תְּלֻאִים לְךָ מִנֶּגֶד; וּפָחַדְתָּ לַיְלָה וְיוֹמָם, וְלֹא תַאֲמִין בְּחַיֶּיךָ״” ↩

- Originally: ״והיא באחת ומי ישיבנה״. See Job 23:13: “Yet He wants but one thing—and who can divert Him? What he desires He will do” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וְהוּא בְאֶחָד, וּמִי יְשִׁיבֶנּוּ; וְנַפְשׁוֹ אִוְּתָה וַיָּעַשׂ״ ↩

- Originally: ״נפש ירעה לו״. See Isaiah 15:4: “Therefore Moab’s picked warriors cry, their life-breath broken up” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); “חֲלֻצֵי מוֹאָב יָרִיעוּ נַפְשׁוֹ יָרְעָה לּוֹ” ↩

- Originally: ״היורדים חדרי בטני כמדקרות חרב״. See Proverbs 26:22: “A grumbler’s words are like pounding and they go down to the belly’s chambers.” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); "דִּבְרֵי נִרְגָּן כְּמִתְלַהֲמִים, וְהֵם יָרְדוּ חַדְרֵי בָטֶן". See also Proverbs 12:18: “One may speak out like sword stabs, but the tongue of the wise is healing” (ibid); ״יֵ֣שׁ בּ֭וֹטֶה כְּמַדְקְר֣וֹת חָ֑רֶב וּלְשׁ֖וֹן חֲכָמִ֣ים מַרְפֵּֽא״ ↩

- Originally: ״פני מרים נהפכו לירקון בדברה״. See Jeremiah 30:6: “Ask, pray, and see, if a male is giving birth. Why do I see every man, his hands on his loins like a woman in labor “and every face turned sickly green?” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״שַׁאֲלוּ-נָא וּרְאוּ, אִם-יֹלֵד זָכָר: מַדּוּעַ רָאִיתִי כָל-גֶּבֶר יָדָיו עַל-חֲלָצָיו, כַּיּוֹלֵדָה, וְנֶהֶפְכוּ כָל-פָּנִים, לְיֵרָקוֹן״ ↩

- Originally: ״נפשה דרכה עוז״. See Judges 5:21: “March on, my being, in valor!” (Robert Alter Bible Translation, titled “The song of Deborah” in KJV and NIV); ״תִּדְרְכִי נַפְשִׁי עֹז״ ↩

- Originally: ״וכל גויתו התנודדה כנוד הקנה במים״. See Kings 1, 14:15: “And the LORD will strike Israel as a reed sways in the water” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וְהִכָּה יְהוָה אֶת-יִשְׂרָאֵל, כַּאֲשֶׁר יָנוּד הַקָּנֶה בַּמַּיִם״ ↩

- Originally: ״עתה אך לשפת יתר יחשב לאמר״. See Proverbs 17:7: “Unfit for a scoundrel, overweening speech, much less for a nobleman, lying speech” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״לֹא-נָאוָה לְנָבָל שְׂפַת-יֶתֶר; אַף, כִּי-לְנָדִיב שְׂפַת-שָׁקֶר״ ↩

- Originally: ״לכי נא עמדי אל ארצי ואל מולדתי״. See Genesis 12:1: “And the LORD said to Abram, “Go forth from your land and your birthplace and your father’s house to the land I will show you” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וַיֹּאמֶר יְהוָה אֶל אַבְרָם לֶךְ לְךָ מֵאַרְצְךָ וּמִמּוֹלַדְתְּךָ וּמִבֵּית אָבִיךָ אֶל הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר אַרְאֶךָּ״ ↩

- Originally: ״מה לי ולגזעך צור ממנו חצבת״. See Isaiah 51:1: “Look to the rock you were hewn from and to the quarry from which you were cut” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״הַבִּיטוּ אֶל-צוּר חֻצַּבְתֶּם, וְאֶל-מַקֶּבֶת בּוֹר נֻקַּרְתֶּם״ ↩

- Originally: ״לשאת עול סבלו ואת מטה שכמו״. See Isaiah 9:3: “For its burdensome yoke the rod on its shoulders, the club of its oppressor—You smashed, as on the day of Midian” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״כִּי אֶת עֹל סֻבֳּלוֹ וְאֵת מַטֵּה שִׁכְמוֹ שֵׁבֶט הַנֹּגֵשׂ בּוֹ הַחִתֹּתָ כְּיוֹם מִדְיָן״ ↩

- Originally: ״ויתנשא כארי״. See Number 23:24: “Look, a people like a lion arises, like the king of beasts, rears up” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); הֶן-עָם כְּלָבִיא יָקוּם, וְכַאֲרִי יִתְנַשָּׂא; ↩

- Originally: ״כי ראה כי נכזבה תוחלתו״. See Job 41:1: “Look, all hope of him is dashed, at his mere sight one is cast down” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״הֵן-תֹּחַלְתּוֹ נִכְזָבָה; הֲגַם אֶל-מַרְאָיו יֻטָל״. ↩

- Originally: ״שבט נוגש״. See FN 21 (Isaiah 9:3). ↩

- Originally: ״המעין הנרפש אשר בתוך עורקיך נובע״. See Proverbs 25:26: “A muddied fountain, a fouled-up spring—a righteous man toppling before the wicked” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״מַעְיָן נִרְפָּשׂ, וּמָקוֹר מָשְׁחָת--צַדִּיק, מָט לִפְנֵי-רָשָׁע״ ↩

- Originally: ״כנים דבריך תזכה בשפטך״. See Psalms 51:6: “You alone have I offended, and what is evil in Your eyes I have done. So You are just when You sentence, You are right when You judge” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״לְךָ לְבַדְּךָ חָטָאתִי וְהָרַע בְּעֵינֶיךָ עָשִׂיתִי לְמַעַן תִּצְדַּק בְּדָבְרֶךָ תִּזְכֶּה בְשָׁפְטֶךָ״ ↩

- See FN 14 (Proverbs 26:22). ↩

- Originally: ״בודדה וגלמודה תעמוד בתבל כערער בערבה״. See Jeremiah 17:6: “And he shall be like an arid shrub in the desert, and he shall not see when good things come” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וְהָיָה כְּעַרְעָר בָּעֲרָבָה, וְלֹא יִרְאֶה כִּי-יָבוֹא טוֹב״ ↩

- Originally: ״נלאתי נשא את דבריך הנעימים, כלכל לא אוכל אותם״. See Jeremiah 20:9: “And I thought, “I will not recall Him, nor will I speak anymore in His name.” But it was in my heart like burning fire shut up in my bones, “and I could not hold it in, I was unable” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״וְאָמַרְתִּי לֹא-אֶזְכְּרֶנּוּ, וְלֹא-אֲדַבֵּר עוֹד בִּשְׁמוֹ, וְהָיָה בְלִבִּי כְּאֵשׁ בֹּעֶרֶת, עָצֻר בְּעַצְמֹתָי; וְנִלְאֵיתִי כַּלְכֵל, וְלֹא אוּכָל״ ↩

- Originally: ״וכזרם מים כבירים זורמו וישטפו דמעות שליש על לחייה״. See Isaiah 28:2: “like a current of mighty rushing waters, He brings down to the earth” (Robert Alter Bible Translation); ״כְּזֶרֶם מַיִם כַּבִּירִים שֹׁטְפִים, הִנִּיחַ לָאָרֶץ—בְּיָד״; See also Psalms 80:6: “You fed them bread of tears and made them drink triple measure of tears” (Ibid); ״הֶאֱכַלְתָּם, לֶחֶם דִּמְעָה; וַתַּשְׁקֵמוֹ, בִּדְמָעוֹת שָׁלִישׁ״ ↩

Commentary

Grace Aguilar, Yeshayahu Gelbhaus (translator), “The War of Faith and Love,” 1874. Commentary by Naomi Brenner

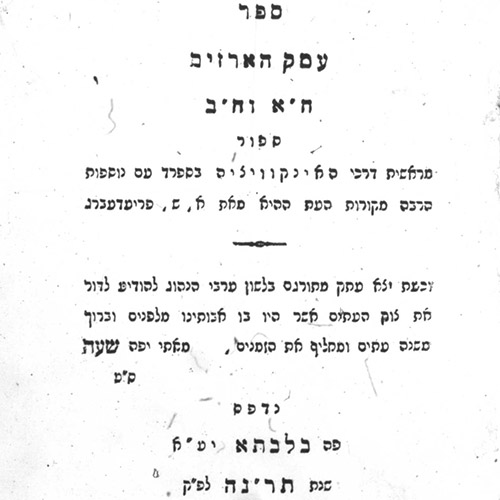

“Faith and Love” is the second installment of a serialized novel that was published below the line in the Hebrew weekly newspaper Ha-levanon (Lebanon) from August 1874 to April 1875. Founded in Jerusalem in 1863 and later published in Paris, Mainz and London, Ha-levanon was one of the first Hebrew papers to set aside space for the feuilleton, in a section titled “Yarketei levanon” (“The Edges of Lebanon”) starting in August 1871. But in contrast to other European Hebrew papers like Ha-melits, Ha-levanon primarily dedicated the space below the line to roman feuilletons, novels that were often translated from the German-Jewish press and printed in regular installments. In this case, each installment was prefaced by the words “copied from a foreign language by Yeshayahu Gelbhaus,” a German Jewish writer and translator also known as Sigmund Gelbhaus (ca. 1850-1928). The text, however, does not mention that it is a translation of Grace Aguilar’s (1816-1847) popular novel The Vale of Cedars, which was written in 1834 but published in 1850, a few years after the English-Jewish writer’s death.

Read Full

For readers of nineteenth century European Jewish novels, “Faith and Love” would likely seem familiar. The first installment introduces readers to the noble Arthur Stanley, bravely crossing the Sierra Toledo mountains in Spain to reach a lovely woman hiding in a remote vale of cedar trees. Many nineteenth century German-Jewish historical romances were set in Spain, often during the Inquisition, emphasizing Jewish faith and heroism as they sought to insert Jews into popular German narratives of the time, which used the fanaticism of the Spanish Inquisition to celebrate the Protestant world’s civilization and tolerance (Hess, 36).

The roman feuilleton’s second installment, featured here, introduces readers to the lovely and courageous Miriam, who dramatically confesses her Jewish identity to Stanley, shocking him and testing his allegiance to the Spanish crown. While Stanley accedes to Miriam’s insistence that he must leave, he is unwilling to accept her refusal to marry him, setting up the narrative twists and turns that follow. These are all familiar features of popular fiction in the tradition of Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) and Eugene Sue’s popular The Mysteries of Paris (1842-3): beautiful young women in danger, evil villains, heroic knights, and love deferred. In its adaptation as a roman-feuilleton, “Faith and Love” also has one of the most important features of this sort of serialized fiction: the words “to be continued” (ha-hemshekh yavo) at the very end of this and subsequent installments. Whether published weekly, as was the case with this feuilleton, or daily, roman feuilletons aimed to keep readers eagerly awaiting to buy the next paper so that they could read the next installment.

Most roman feuilletons were initially published in the press and, if they were well received, later republished in book form. The Vale of Cedars, however, was initially published as an English novel and then was transformed into a Hebrew roman feuilleton which was also republished as a book a few years later. Ha-levanon acknowledges that this text was translated, but provides no details about the original text, author, or language. Perhaps the editors of this Orthodox publication were hesitant about attributing the text to a woman, even a highly regarded Jewish woman writer. Perhaps they were unaware of the connection to Aguilar, since Gelbhaus’s translation was based on J. Piza’s German translation, published as Marie Henriquez Morales (1856) and Das Cederenthal (1857). Perhaps they did not care about the origins of the text, publishing in a time in which popular fiction was often reproduced without crediting authors or translators. In any case, Gelbhaus’s Hebrew version was reprinted as a novel in 1875, the same year that Avraham Shalom Freidberg (1838-1902) published his own Hebrew translation, titled Emek ha-arazim (The Vale of Cedars) in Warsaw. Over the next few decades, free translations of Aguilar’s work appeared in other Jewish languages, including Di ungliklekhe Miriam (The Unhappy Miriam) in Yiddish in Vilna in 1888, Emek ha-arazim (The Vale of Cedars) in Judeo-Arabic in Calcutta in 1892-1893 and Qissat al-Yahud fi Ispaniya (The History of the Jews in Spain) in Judeo-Arabic in Tunis in the 1930s. The translations and transformations of The Vale of Cedars demonstrate the broad circulation of this and other popular roman feuilletons across Europe and across global Jewish cultures.

Sources:

- Grace Aguilar, The Vale of Cedars, or The Martyr (1850).

- Jonathan Hess, Middlebrow Literature and the Making of German-Jewish Identity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010).

Further Reading:

- Janine Strauss, “From The Vale of Cedars by Grace Aguilar to Emek ha-arazim by Abraham Shalom Friedberg,” (Hebrew) in Ha-kenes ha-ivri ha-mada’i ha-shelosh-esraeh be-eiropa universtitat Madrid, ed. Menahem Zohori (Jerusalem, 2001), 93-98.