Explore Feuilletons

The Valley of Cedars

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

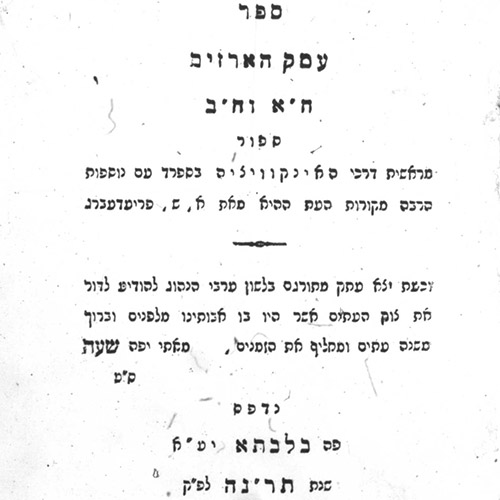

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Related Text

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Grace Aguilar, Solomon Twena (translator), “The Vale of Cedars,” 1892. Translated by Lital Levy

One of the guards walked with him, lighting the way ahead of him until they reached the door of the chamber where Sebastian was imprisoned. The guard unlocked the door. The doctor (al-daktur) took the lamp and told him to take care of his business and come back in an hour. Over a worm-ridden mound of hay giving off a stench of rot, surrounded by garbage, was a pile of torn rags left atop a naked and beaten-up body. Its face is white, drained of blood; its eyes are darkened; the hair on its head has gone white; its toes and feet are smashed.

Read Full

Trembling and shivering, the doctor bent down towards the body, his strength failing from the fearful sight. He began weeping behind his face cover, and lamented: “Is this really Sebastian the hero (Ma hadha huwwi Sebastian al-gibor)? Is this the end of all heroes in our clan, in this country ruined by sycophants and informers? Ya hayf – For shame. The precious sons of Zion, comparable to fine gold, how are they esteemed as earthen pitchers, the work of the hands of the potter!”1

Just then, he pulled a flask from his pocket, rubbed some of it on his temples and applied it to his nostrils. When the wounded man smelled the perfume’s fragrance, he came to and roused himself from the sleep of death brought upon him by his great injuries and pains. He sighed, took a breath, and shouted in a weak voice, “Water! All my joints are burning.” The doctor poured some liquor into his mouth. At that moment, his spirit returned to him and his eyes lit up like the light of the lamp in his cell. But when [the doctor] lifted the cover from his face, he was stricken with fear and his eyes darkened. The doctor’s heart fired up inside him, and his joints began to shake. Such was his distress that he forgot about those standing nearby; he cried out from the depths of his heart, and began to recite the lamentation of Rabbi Judah Halevy:

“How can I take pleasure in food and drink When dogs are dragging your lions with their teeth? How can the daylight to my eyes be sweet When those eyes see eagles caught in ravens’ beaks?”

The voice wasn’t strange to the wounded man. At that moment he opened his eyes to see who among his friends and acquaintances2 was covering himself with a wrap and walking disguised in these caves. Just then, the doctor removed the covering from his face.

“Julian!” the wounded man shouted. “Sebastian, my uncle!” the doctor cried, kissing his uncle’s cold hand. “Woe to me (ya wayli) that I’ve seen you in this frightening state.” “How lucky I am, my nephew, that you saw me like this,” the wounded man replied, “since God, may he be praised (ha-shem yitbarakh), fortified my heart, and I did not reveal your secret even in my distress.” Julian could not restrain himself and began sobbing upon his poor uncle (‘ala ‘ammo ya miskin).

Julian’s soul could not stand firm against the grief, heartache, and heavy sobs. Sebastian asked him, “Why did you abandon the Vale of Cedars (Emek ha-Arazim), what brought you here, and what is your business in this oppressive place?”

Julian told him, “Give me some time and I will come back to all your questions.” He soothed his heart, and then spoke to him, saying, “As you know, ever since I saw my hope parting from the world, I made my heart give up on the life of toil in this world. It was my intention to seek out and find the path of the padres and their corrupt deeds in order to take my revenge and extract vengeance from them for the killing of my father, and today it has been twelve years. It has been twelve years since I left the Vale of Cedars, and from that day until this very moment I have been wandering in this world. I’ve given up even my eyes’ sleep to redeem my father’s blood from his killers’ hand, since my father’s blood howls to me from this accursed land. Woe, woe! For what did they fill up the ground (erets) with our blood? There is in it the blood of our glorious brothers, who gave their souls up to death for the sake of the Lord, may He be praised (‘ala kedushat Hashem yitbarah), and for the succor of their forefathers. And today I have been wandering for a month in the caves of these people in order to fulfill my purpose.

To my great misfortune, I saw how these unjust people brought you here and how you were counted among the holy men of our people (al-maqdishun li-ahal qawmuna). My eyes witnessed your torture, and how you gave nothing away, revealing neither your nephews’ hideout nor their hidden property. Seeing you like this, my heart shattered inside me, my insides howl like the roaring sea, because I am flesh of your flesh and bone of your bones, and they crushed your flesh and your bones. They tore your body apart like old rags and showed you no mercy. Woe to me (ya wayli)! How can I live after seeing what I’ve seen? How can I console myself after what my ears have heard?”

“You still have time, my nephew, to cry over me, to lament your poor uncle, who is being tortured with a broken soul. However, it is for my house that I had to suddenly abandon that my heart screams. I did not counsel them, nor bless them. How can I do something for my poor family? And what will become of the affairs of my only son? Who will inform him and explain to him that he is a Jew, descended from the offspring of Judah? Who will make him aware of how to follow my path and walk in the ways of his holy fathers (abhathu al-kedushim)? Who will teach him and lead him in God’s trust (emunat el)? Who will guide him and instruct him in the religion of God and His law (bi-torat el wa-bi-shari‘u)?”

Julian replied: “Calm yourself and do not worry. I will become the father of your house and comfort your poor family. I will take care of your son and keep my eye on him. I will take him with me to the Vale of Cedars, and there I will teach him, guide him, and instruct him the law of God and His religion and faith (bi-shari‘at el wa-fi toratahu wa-al-emanathu).”

“No! No! my nephew. God forbid that you rush into that too quickly, while he may be still ignorant and unable to keep the words hidden in his heart, and would reveal our secret. Our cover will be blown and we will all perish. He is clever, big hearted, and a quick learner. His soul will not be able to contain it, so he will also be brought into these caves, and then who knows how he will end up. I ask of you only one thing, my nephew: that you swear to me by God, if you want to soothe me and settle my spirit and calm my bones before I die, that you will not tell him our secret until he reaches the age of twenty-five, since at that time he will be able to keep it hidden. I know very well that he will grow up, become a man, and inherit the soul of his forefathers. His deeds will raise him to prominence in the eyes of the monarchs and rulers. At that moment, take your time to teach him and show him who he is, who his parents are and what his father’s end was. Immediately, his eyes will be opened, he will see a strong light in this world, and he will be able to carry his anger and his pain and do his work thoughtfully, and will not be hunted into this vicious trap. From this world he must remove these tyrannical judges who rule from underground. Then, my crushed bones will delight that their revenge has been taken, and my heart will rejoice that it saw vengeance. The blessing of a lost and destroyed father, my nephew, will come upon you.”

Commentary

Grace Aguilar, Solomon Twena (translator), “The Vale of Cedars,” 1892. Commentary by Lital Levy

In the 1830s, a young Sephardic Englishwoman named Grace Aguilar wrote a historical romance titled The Vale of Cedars. Set in medieval Spain during the early days of the Inquisition, the work had all the makings of a bestseller: unrequited love, a rich historical setting, political intrigue, a murder, torture, a zero-hour rescue, and vengeance. But unlike other popular English novels, the heroine of this tale is Marie Morales, a crypto-Jewish woman who rejects marriage to a Christian suitor and dies a martyr to her faith. Published posthumously in 1850, The Vale of Cedars was a success. By the end of the century, the novel would make its way into the Jewish-language literary circuit, appearing in Hebrew, Yiddish, and Judeo-Arabic editions.

Read Full

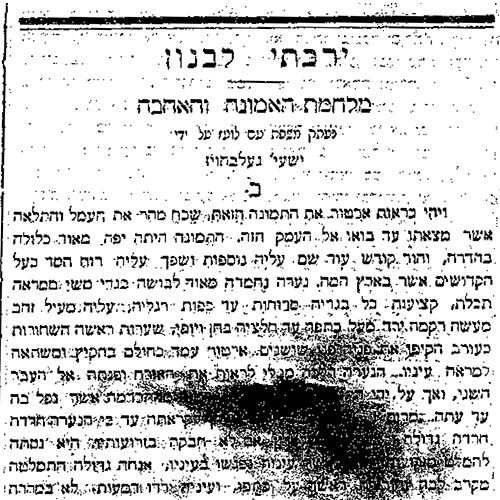

Vale’s transmission into Jewish languages was prefaced by the appearance of the 1857 German edition, which was warmly received by Germany Jewry. J. Piza’s free adaptation pared down Aguilar’s novel, producing a version more easily adapted into modernizing literary languages. From this German version, The Vale of Cedars then appeared in Hebrew in two separate and independent editions. One version, retitled “Ha-emunah ve-ha-ahavah” (“Faith and Love”), first appeared as a roman feuilleton in the Hebrew weekly The Lebanon (Mainz) from 1874-1875 without attribution to Aguilar. Sigmund Gelbhaus, the translator, also published the complete translation as a book in 1875. That same year, the Hebrew writer Avraham Shalom Friedberg published his own translation as a book in Warsaw (reissued in 1893), titled Emek ha-arazim (The Vale of Cedars) and attributed to Aguilar. Friedberg’s version added a short historical prologue about the Inquisition and a lengthy new first chapter that creates a new backstory for the plot. It also introduces Pedro, a new Jewish male protagonist who replaces Marie’s Gentile love interest, and recenters the novel around Pedro’s story. Friedberg’s version shaped the novel’s reception throughout the Jewish world; it was adapted into Yiddish and Judeo-Arabic as well as two modernized and abridged Hebrew editions (1954 and 1970). The Yiddish version, Di ungliklekhe Miriam (The Unfortunate Miriam), was printed in Vilna in 1888 and reprinted in 1910.

In the same year (1888), the first of the two Judeo-Arabic translations was undertaken by the Tunisian Jewish polymath Jacob Chemla, a key figure in the Maghrebi Haskalah. An important translator and journalist, Chemla edited the Judeo-Arabic journal El-Boustan (The Garden) from 1892 to 1897. His translation appeared as a feuilleton in El-Boustan from 1888 to 1889; in the 1930s it was republished in Tunis as a book titled The History of the Jews in Spain (Qissat al-Yahud fi Ispaniya). Chemla’s version follows Friedberg, though the title page mentions neither Friedberg nor Aguilar. His translation Arabicizes of all the Hebrew elements of Friedberg’s additions, and adds popular Arabic poetry characteristic of North African Jewry as well as several digressions into different episodes in Jewish history. Chemla’s translation choices suggest that he aspired to stoke the communal sympathies and religious fervor of his readers and points to their lack of Hebrew literacy.

Meanwhile, at the other far end of the Judeo-Arabic speaking world, the Calcutta-based rabbi Solomon Twena printed his own translation as a feuilleton in the literary supplement of his Judeo-Arabic newspaper Magid mesharim (The Speaker of Truths) from 1892 to 1893, and again as a two-volume book in 1894-1895. Twena served the expatriate Baghdadi community employed in British trade in Asia; his Magid mesharim was one of several Judeo-Arabic newspapers published by Baghdadi Jews in India during the second half of the nineteenth century. It appeared weekly in Calcutta from 1890 to 1900 and carried news of Jews in Baghdad as well as local news of Jewish communities in India, announcements of births, deaths, and marriages, shipping news and schedules, and worldwide Jewish news. It also contained a literary supplement, Magid mishneh, that appeared as a full-page section toward the end of each issue. In this feuilleton, Twena printed a wide range of cultural sources including literature translated from Hebrew and other languages, folk stories, and his own Hebrew sermons. Twena’s literary supplement was intended to enrich the cultural and spiritual lives of his male readership, Iraqi Jewish merchants in Iraq, India, Burma, Hong Kong, and elsewhere in Asia.

A fairly literal translation of Friedberg’s text into the Baghdadi Jewish dialect of Arabic, Twena’s version of The Vale of Cedars preserved the Hebrew titles, biblical quotations, and intertextual literary elements such as verses by the medieval poet Judah Halevi, suggesting that his readership was equally comfortable with both Hebrew and Arabic. The selection presented here is excerpted from Twena’s translation of the new material added by Friedberg. In this dramatic scene, Julian, a Jewish man disguised as a Christian doctor, finds his uncle Sebastian, Pedro’s father, dying in the underground torture chambers of the Inquisition. Pedro has been raised as Christian nobility and is unaware of his paternal Jewish lineage. Julian promises Sebastian on his deathbed that when Pedro comes of age (on his twenty-fifth birthday), Julian will reveal the secret, instruct Pedro in the tenets of Judaism, and bring him to the Vale of Cedars, his Jewish family’s hidden home. I have added parenthetical notes to show how Twena uses both colloquial Arabic and liturgical Hebrew in his narrative prose.

Further Reading:

- Yitzhak Avishur, “Sifrut ve-'itona'ut ba-'aravit yehudit shel yehudey bavel be-defusey hodu," (“Judeo-Arabic literature and journalism of Babylonian Jewry in Indian presses"). Pe'amim 52 (1992): 101-15.

- Yitzhak Avishur, Ha-hakham ha-Bavli mi-Kalkuta: Hakham Shelomo Twena vi-yetsirato ha-sifrutit be-‘Ivrit u-ve-‘Arvit Yehudit (The Baghdadi Rabbi from Calcutta: Rabbi Shlomo Twena and His Works in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic), (Tel Aviv : Pirsumey Merkaz arkheʼologi : "Magen Avot" li-yehude Kalkuta, 2002).

- Yosef Tobi and Tsivia Tobi, Judeo-Arabic Literature in Tunisia, 1850-1950 (Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 2014).