Explore Feuilletons

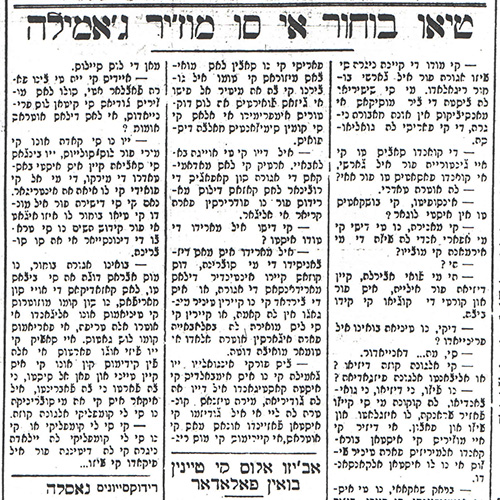

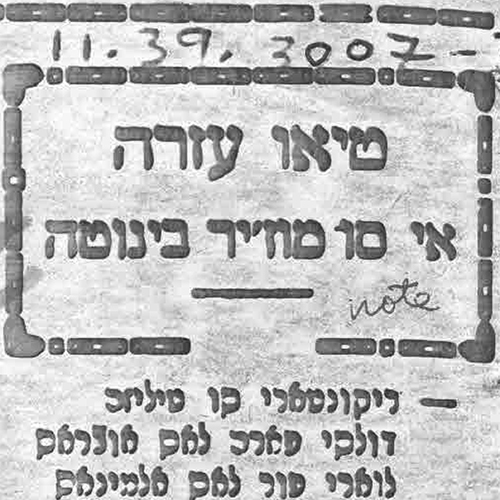

Uncle Bohor and His Wife Djamila

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Related Text

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Moshe Cazes, “Uncle Bohor and His Wife Djamila,”1 1939. Translated by Marina Mayorski

[…] - Djamila: Did I tell you that I was there when my sister’s daughter had an abortion? - Bohor: And? - Djamila: And I went to see her. They were saying that her life was hanging by a thread and she barely survived. - Bohor: What for, did her pregnancy not go well? - Djamila: Yes, but… I’m so angry I could burst. - Bohor: What, was it something she wanted? Or did she lift a heavy load? - Djamila: No, my boy, no wants, no nuts. The floozy lady wanted to make herself European (fazer franka), so the child was devoured by a peacock. And to think that there are women that are turning the whole world upside down to have children and cannot have them. - Bohor: Stop joking around – I don’t understand you. What do you mean – he was devoured? - Djamila: Dear God, what is so difficult for you to understand, Bohor. Don’t you know that now it is the vogue among the modern little madams (madamikas) who don’t want to feel the pains of birth nor to raise children? - Bohor: And? - Djamila: And, she got up, this devil of a woman, went to who knows what demon of a doctor and the child was devoured. - Bohor: From your mouth to God! Did she really do that, the bastard (mamzera), by her own doing? Bravo to their “Europeanness” (frankedad) for the baggage that these little madams took up and brought all that is wicked these days. But it seems that those no-good scoundrels don’t know about the new measures that the government is taking, that will first bring down heavy fines on the doctors and later on the women that do such things2. - Djamila: May God hear you, dear husband. In the end, the little madams can ruin their husbands’ households by not being able to give birth and nurse. - Bohor: What did the husband say about all this? - Djamila: The husband is even more full of nonsense than my niece. There are two things I want to understand about today’s so-called husbands: either it is true that they do not want anything “happening” in the bedroom, or they want the lady of the house to die so that another one will lie down in her place and they will take a new dowry. - Bohor: Do you see why I am disgusted, Djamila, because it is not for nothing that God has cursed the Jewish people. See how they taint the Jewish law and tradition, some more than others, and we want the heavens to take pity on us. […]

- This feuilleton was first located, studied, and transliterated from Hebrew (“Rashi”) script into Latin script by David Bunis. See: David M. Bunis, Voices from Jewish Salonika: Selections from the Judezmo Satirical Series Tio Ezrá i su mujer Benuta and Tio Bohor i su mujer Djamila (Jerusalem and Thessaloniki, 1999), 474–5 (no. 58). Translated from Ladino into English by Marina Mayorski. Both texts were reselected for the feuilleton project by Tamir Karkason, who also edited the translation. We sincerely thank Prof. David Bunis for his support and for providing us with the original texts. ↩

- Literally: “eat such halva.” ↩

Commentary

Moshe Cazes, “Uncle Bohor and His Wife Djamila” and “Uncle Ezra and His Wife Benuta,” 1939. Commentary by Tamir Karkason

These two satirical feuilletons were written by Moshe Cazes (1889/90–1942/3) of Salonica in the late 1930s. The feuilletons, collected and published by David Bunis (1999), feature the fictional characters Uncle Ezra (or Bohor) and his wife Benuta (or Djamila) and reflect life in Jewish Salonica. Since several thousand people bought copies of newspapers Aksyon (An Action, 1929–1940) and Mesajero (A Messenger, 1935–1941) each day, the heroes of Cazes’s pieces must have been the talk of the day in Jewish Salonica at the time.

Read Full

In 1912, Greece conquered the Ottoman city of Salonica, which was home to some 80,000 Jews. During the period of Greek rule, the texture of Jewish life in Salonica changed dramatically; from one of many ethnic groups in the Ottoman state, the Jews became a small national minority in the Greek state. The Salonican Jews, who had constituted a majority in the city during the Ottoman period, were forced to cope with laws and regulations initiated by the state that sought to strengthen the Hellenic character of the country. The life of the Jews in Greece was not entirely negative, and Hellenization also brought a remarkable flourishing of Greek-Jewish culture, but in the final analysis, the years of Greek rule were certainly complex for the Jews of Salonica (Naar 2016).

Following the Greek occupation of 1912, three intellectual and social groups dominated Jewish life in Salonica: The Socialists, the Zionists, and a group identified with Westernization and Hellenization (Naar 2016, 23–24). But there were also Salonican Jews who avoided politics and ideology, maintained religious observance, and were familiar with the traditional literature in Ladino. Fortunately, we have evidence from the last possible historical moment in the form of the satirical feuilletons written by Cazes on the eve of World War II.

Cazes was himself the son of a lower-class religious family, who had both a religious and a modern education, and was also a popular singer as part of a duo called Sadik and Gazoz. Cazes’s satirical articles, which emphasized the tension between traditional Jews and Westernizers, provide a window into the lives of the ordinary Jews who are absent from almost all the other sources. The feuilletons mock the older generation of Jews, those born between the 1860s and 1880s, while ironically identifying with their inability to cope with the changes of the late 1930s.

In the first piece, Ezra, a consumer of Ladino religious literature, read aloud on the holiday of Shavuot the Azharot (Exhortations) of Ibn Gabirol, translated into Ladino in 1742. But his illiterate wife, Benuta, assumes that the language he was reading was not Ladino at all, and certainly not the spoken Ladino the couple used, but rather Arabic – the language of the closest “other” in the post-Ottoman society. Cazes’s satire mocks both the male figure, who is portrayed as overly devout in his religion and practices in a world of increasing secularism, and the female one, for whom an archaic component of her mother tongue seems completely foreign. Almost thirty years into the era of the Greek state, the archaic Ladino that Benuta mistakenly perceives as Arabic brings her back to the bygone Ottoman world from which she – no less than her husband – has been unable to completely disengage.

The processes of modernization and secularization are even more evident in the second piece, where Djamila informs her husband Bohor – similarly, a new name for Ezra – that her niece has chosen to have an abortion. While Djamila has replaced Benuta and Bohor has replaced Ezra in this feuilleton, Cazes’s style and plot are nearly identical to the previous example. Bohor was shocked at the news, as a religious Jew who had never encountered the concept of family planning; as for Djamila, she was not shocked by the abortion itself, but felt sorry for infertile women. This piece illustrates that although Djamila and others like her were raised in conservative homes and rarely left their confines, they were more open-minded and liberal than their male counterparts and displayed an impressive measure of agency as women.

Unfortunately, Cazes and Salonican Jews like Ezra, Benuta, Djamila, and Bohor would suffer a bitter fate just a few years later, when the Jewish community of Salonica and its unique and irreverent culture were annihilated during the Hollocaust. May their inclusion in the feuilleton project help perpetuate their memory.

Further Reading:

- David M. Bunis, Voices from Jewish Salonika: Selections from the Judezmo Satirical Series Tio Ezrá i su mujer Benuta and Tio Bohor i su mujer Djamila (Jerusalem and Thessaloniki: Misgav Yerushalayim, the National Authority for Ladino Culture, and Ets Ahaim Foundation of Thessaloniki, 1999).

- Devin E. Naar, Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016).