Explore Feuilletons

[On Antisemitism]

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Date Issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Related Text

Keywords

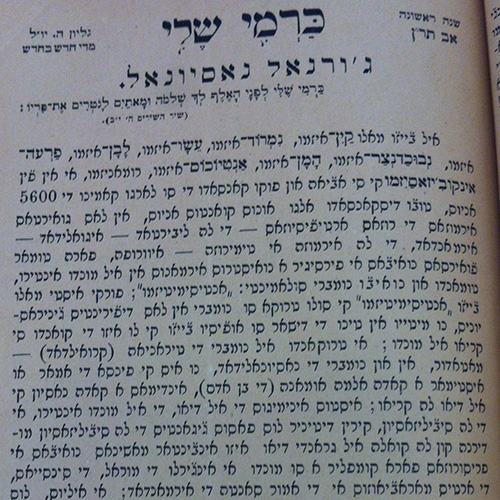

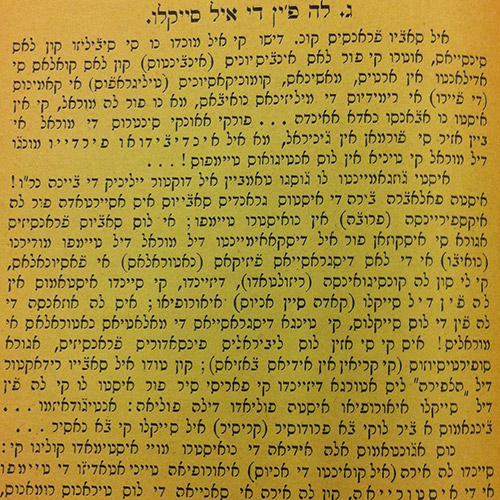

Original Text

Translation

Barukh Mitrani, “[On Antisemitism],” 1890. Translated by Tamir Karkason1

The old evils – Cainism, Nimrodism, Esauism, Lavanism, Pharaohism, Nebuchadnezzarism, Hamanism, Antiochusism, Romanism2, and finally Inquisitionism – that left us a little tired after a long journey of 5600 years, took a pause for a few years, in the fine gardens of the artificial roses of liberty, equality, and fraternity in beautiful and mighty Europe. But this was only in order to gain new strength to persecute our brethren around the world, while merely assuming a new name: “antisemitism.”

For this old woe of “antisemitism,” which has changed its name throughout the generations, had no intention of abandoning its old profession, which it developed ever since the world was created; and by changing the name of tyranny, it murders in the name of nationality, and does not think of loving or admiring every human soul (of ben adam), every nation, as created by God.

These enemies of God, of the entire world, and of civilization, wish to hamper the enormous steps that are being taken by modern civilization, which the great God led to invent new and speedy machines to maintain His world and to fill it with morality, science, wonderful arts, and a sacred love of brotherhood. And these evil enemies wish to fill it with darkness and cruelty. But the great God, blessed be He and blessed be His name, is forever a merciful God, Father of the universe, loving Father of Israel; He will not bring His world to oblivion because of some evil and feeble-minded fools! […]

Commentary

Barukh Mitrani, “[On Antisemitism],” 1890, and “The End of the Century,” 1891. Commentary by Tamir Karkason

These two feuilletons were written in Ladino by the Ottoman maskil Barukh Mitrani (1847–1919), who lived at the time in Edirne, in the northwest of what is now Turkey, in his periodical Karmi sheli (My Orchard, Pressburg and Vienna, 1890–1891).

Just as synagogue sermons create connections between the Jewish sources and current events, newspapers also address contemporary developments in constantly changing ways. Thus the emergence of the Jewish press in the nineteenth century soon led to a realization of the similarities between the medium of the sermon and the medium of newspapers, especially in the new form of the feuilleton. Mitrani, who was born in Kırk Kilise in eastern Thrace (today Kırklareli, Turkey), and wandered between Southeastern Europe, Istanbul, and Palestine, was the maskil who most clearly demonstrated the connection between the sermon and the press in the Ladino cultural sphere.

Read Full

Between the 1860s and the 1890s, Mitrani published a wide range of material in Ladino and Hebrew, including hundreds of articles in Hebrew-language newspapers based in Europe and Palestine. From the 1880s he founded several Ladino or bilingual (Hebrew and Ladino) publications in which sermons played a central role.

Mitrani preached in synagogues on an occasional basis. While settling in Sofia (now in Bulgaria) he wrote: “And therefore the dear journals […] will be more useful than ten sermons of fatigued preachers. For new matters and articles from a distant land will stir up and awaken much more than the local preacher does in his sayings alone” (“Ivri Anochi,” February 16, 1877). It is not surprising to find that the issues of Mitrani’s first journal, Karmi, in the early 1880s took the form of an ongoing maskilic sermon, and a decade later Mitrani published in his Karmi sheli several articles I have identified as Ladino feuilleton sermons: a hybrid version of the feuilleton which essentially employs a “modern” form of a “traditional” tool to criticize modernity.

As a rabbinic maskil, the medium of the feuilleton sermon allowed Mitrani to express his whole intellectual personality, in which “tradition” and “modernity” were interwoven. In the first text, “On Antisemitism” (1890), he connects the anti-Semites of his own days with biblical and other ancient figures such as Pharaoh, Haman, and Antiochus, and used the suffix “-ism” (-izmo in Ladino) to identify them. The historical “hatred of Israel” and the so-called modern “antisemitism” were entangled in Mitrani’s thought. Ironically, the form of the feuilleton, which was increasingly perceived as a Jewish form by antisemitic writers, served Mitrani to discuss the phenomenon of antisemitism.

In both texts, and specifically in the second text, “The End of the Century” (1891), Mitrani claims that moral standards were failing to keep pace with technological developments, and does not hesitate to quote French intellectual such as Nicolas de Condorcet, as well as two European Jewish intellectuals, Adolf Jellinek and Nahum Sokolow, “the wise editor of HaTzefirah.” However, he criticizes the modern age as one in which antisemitism had found its place “in the fine gardens of the artificial roses of liberty, equality, and fraternity in beautiful and mighty Europe.”

Barukh Mitrani combined his rabbinic background and Jewish observance with an openness to Ottoman and Western modernity. He was therefore a prototypical figure of the Ottoman maskil, who differed from “Westernizers,” supporters of the Alliance israélite universelle who were dominant in the popular Ladino press, on the one hand, and from some Ultra-Orthodox circles that sought to withdraw from teaching “secular” studies such as science and foreign languages, on the other (Karkason 2021). In his Sephardi identity and residence on the margins of Europe and Asia, Mitrani also differed from most Hebrew writers and readers of the time. Although he perceived himself as an integral part of modern Hebrew culture, he also felt that Central and Eastern European Jewish intellectuals excluded him and his Ottoman peers. In light of the unique story of this wandering maskil, who sought a bridge between East and West in the nineteenth century Jewish diaspora, it is no wonder that Mitrani’s texts are emblematic of the hybrid medium of Ladino feuilleton sermons.

Further Reading:

- Aron Rodrigue, “Jewish Enlightenment and Nationalism in the Ottoman Balkans: Barukh Mitrani in Edirne in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century Minorities in the Ottoman Empire,” in Minorities in the Ottoman Empire, ed. Molly Greene (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2005) 129–143.

- Michael Studemund-Halévy, “Ivri, Daber Ivrit! Baruch Mitrani, a Turkish Sefardic Maskil in Vienna,” Transversal 13, no. 2 (2012): 9–39.

- Tamir Karkason, “Between Two Poles: Barukh Mitrani between Moderate Haskalah and Jewish Nationalism,” Zutot 18 (2021): 1–11.