Explore Feuilletons

From the Handwritten Diary of a Woman from the 17th Century

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Abraham Tendlau, “From the Handwritten Diary of a Woman from the 17th Century,” 1864. Translated by Matthew Johnson

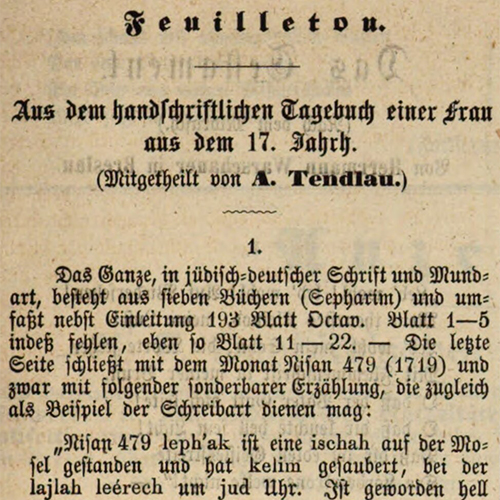

Feuilleton

From the Handwritten Diary of a Woman from the 17th Century

(Imparted by A. Tendlau)

1.

The whole, in Jewish-German writing and vernacular, consists of seven books (Sepharim) and comprises 193 pages, octavo format, along with an introduction. Pages 1-5 are missing, as are pages 11-12. —

Read Full

The last page closes with the month Nisan 479 (1719)1 and, to wit, with the following strange story, which may also serve as an example of the writing style:

“In Nisan 479 leph’ak2 [5479] an ishah [woman]3 stood on the Moselle and washed kelim [dishes] at laylah [night] leérech [approximately] at yud [ten] o’clock. It became light as if it were day and the sky was open as if — — — and sparks flew from it and then the sky closed again, as if someone had drawn a curtain, and it became completely dark again. Hashem Yitbarach baruch hu [God, blessed be He] shall give that it be letovah [good]. Amen and amen.”

This last page was written by a different hand with the note in the margin: “I have supplemented this pagina from the other original. The three dashes indicate where a word is missing, which I could not make out because it was already very metushtosh (stained) and torn because of its age. Today (hayom etc.) on the 4th day, the 13th Kislev 560 (1800). Chaim ben Joseph Homel ségal (Levite) sézal (blessed memory) physician (rophe etc.) in the holy community Frankfurt am Main. —”

The content of the book deals with the history of the author’s own family as well as with remarkable events near and far, e.g., events from the year 1666 in relation to Shabbetai Zvi. Here and there are heartfelt admonitions, directed to the children of the author, to live a godly life, which are interwoven with didactic stories, fables, sayings and the like from books and from experience. The books that she expressly recommends her children read are several siphre mussar [pietistic books] by R. Abraham Shabthai Hallevi (?),4 and for those who do not understand (“cannot learn”) Hebrew, the Yiddish Brandspiegel (also called sefer hammáreh by R. Moshe Henoch. Basel 1602. 4. Frankfurt 1677, 4.) and the Lev tov (by R. Yitzchak. Wilmersdorff 1673 fol.).

The author, with the name of “Glück” or “Glücklich,” was born in Hamburg in 1645. Her father was, as she tells it, a good and respected man, “a very considerate Parnes [elected member of the Jewish community council] of the community,” who, however, with the other prominent community members, confronted envious and hateful opponents, who even persecuted him in front of the King of Copenhagen, albeit in vain. In her twelfth year, she became engaged and, in her fourteenth (1659), married a widower named Chajim Homel (from Hameln, thus the surname Homel-Goldschmidt in Frankfurt of one of her sons named Isak, who settled in Frankfurt ). Her father-in-law’s name was Joseph Homel, whose father, Samuel Stockert, “was Parnes in all of Hesse”; her mother-in-law, named Freuden, was the daughter of Nathan Spanier from Stathagen. — After becoming a widow in 1689, she married for a second time in 1693 to a man named Hirsch Levi in Metz, albeit unhappily.

That the author enjoyed, in the house of her parents, a more than typical education for the time is evident — apart from the very idea and writing of a diary — from some of what she imparts in the introduction about earlier events in her family. Among other things, she reports: Her grandmother, named Mate, became a widow early on, seemingly as a result of a specific morbidity that snatched away many respected men in Hamburg — p. 22 names the Parnes Feibelmann, a Chaim Fürst, the richest in the community and also Parnes, then Abraham Shamesh, who, before his soul ran out, said: “I have been called before the council and the high court to bear witness,” and also the son of Chaim Fürst, named Salomon, who was a tax collector (gabbai), and still others, by which, as she says, God changed the fight with the Parnosim. After the grandmother married her daughter Olk to Jakob Reh, she had little left, and she felt compelled to move into the house of her son-in-law Jakob Reh with her eleven-year-old daughter, the mother of the author.5 The eleven-year-old girl was particularly good at the art of making silver and gold lace. Jakob Reh vouched for his mother-in-law at first, and since the work was delivered in good condition and on time, the merchants had full confidence in it, so that the young girl, with other girls who were given lessons, could provide for herself and her mother, meagerly but honestly, decent food and clothing. — Later, this girl married a widower who had only one daughter, namely a stepdaughter whom his first wife named Reize — “who is said to have been an upright person and great gebartanith (of firm character)” — “and who had no equal, both in beauty and in action, and who could speak French like water,” which — as the author tells it — was once very useful to her father. “My father of blessed memory,” she narrates — “had a pledge from a magistrate (rosh), worth 500 Rthlr [Reichstaler]. After some time, the magistrate comes with two other magistrates to redeem the pledge. My father of blessed memory, who thought of nothing bad, goes up to get the pledge. His daughter stands by the clavicymbel [a keyboard instrument, likely similar to a clavichord] and plays it so that the men do not have to waste time. The men stand near to her and talk to each other: If the Jew returns with our pledge, we will take it without paying and leave. They said this in French and didn’t think that the maiden would understand. When my father of blessed memory came with the pledge, she began to sing loudly: Bechaytti lo hamashkon! hayom bekáan, machar vayivrach!” (By my life, no pledge! Here today, tomorrow he’ll run away!) Under these constraints, she could not, nebich [the poor thing!], come up with anything else.6 So my father of blessed memory says to the men: “My sirs! Where is the money?” — “Give me the pledge,” said the man. — “I won’t give you the pledge,” said my father of blessed memory, “I need to have the money first.” — Then one of the men said to the others: “Brothers! We have been betrayed! The … must understand French!” and with three words they run out of the house.7 — The next day the magistrate comes alone and gives my father, of blessed memory, capital and interest for the pledge and says: “You have been able to enjoy it very much and invested your money well by letting your daughter learn French.”

(To be continued.)

- Translations in parentheses () are renderings of glosses that were included in the original, usually for loshn-koydesh (Hebrew-Aramaic) vocabulary. In order to preserve the linguistic textures of the feuilleton, I have not attempted to standardize transliterated words and phrases; instead, the spelling mostly follows that of the original, with occasional minor changes to aid pronunciation for the English reader. ↩

- In the original, the bulk of the text is printed in Fraktur, a type of typeface popular in Germany in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, while many (though not all) loshn-koydesh words are printed in a different typeface. I indicate this difference with italics, even though italics are not used in the original. Emphasis in the original Fraktur, usually rendered with italics, is indicated with bold and italics here. ↩

- Translations included in brackets [] provide glosses that were not included in the original. ↩

- The question mark is in the original. ↩

- Footnote in original: “Olga. — Ueber die jüdisch-deutschen Frauennamen überhaupt s. Sprchwörter und Redensarten.“ von A. Tendlau Nr. 958, S. 332. (Olga - about Jewish German women’s names in general, see “Proverbs and Sayings.”) ↩

- In the feuilleton, Tendlau includes a footnote to the word “nebich” (or “nebekh”), citing his earlier work: “On the origin and meaning of ‘nebich’ or ‘newig,’ see Nr. 633 in Tendlau’s Sprichwörter und Redensarten deutsch-jüdischer Vorzeit (Proverbs and Sayings of the German-Jewish Past, 1860).” ↩

- Ellipses are included in the original feuilleton, though, in the source text, the men refer to Reize as a “hur” (“whore”). See Chava Turniansky’s reflections on this passage in the introduction to Glikl: Memoirs 1691-1719, ed. Chava Turniansky, trans. Sara Friedman (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2019). ↩

Commentary

Abraham Tendlau, “From the Handwritten Diary of a Woman from the 17th Century,” 1864. Commentary by Matthew Johnson

In 1864, the German-Jewish historian and folklorist Abraham Tendlau (1802-1878) published the first installment of a six-part feuilleton with the title “Aus dem handschriftlichen Tagebuch einer Frau aus dem 17. Jahrhundert” (“From the Handwritten Diary of a Woman from the 17th Century”). It was included in the “Beilage” (supplement) to an issue of the Mainz-based newspaper Der Israelit. Ein Central-Organ für das orthodoxe Judenthum (The Israelite: A Central Organ for Orthodox Judaism), founded by Marcus Lehmann in 1860. From the mid-nineteenth through the early twentieth centuries, Der Israelit was one of the leading orthodox publications in the German-speaking world, with editions and supplements also appearing in Hebrew and Yiddish.

Read Full

Lehmann’s newspaper played a key role in the emergence and diversification of the German-language Jewish press that, as Jonathan Hess and other scholars have elucidated, was largely responsible for the popularization of “middlebrow literature,” which shaped modern German-Jewish identity in crucial ways.1 In addition to the publication of such contemporaneous “middlebrow literature,” however, the feuilleton section of this newspaper provided space for the recovery of works of Old Yiddish literature, such as the writings of Glikl bas Judah Leib (ca. 1645-1724), which likewise appealed to the interests and tastes of German-Jewish readers during a time of flux.

Tendlau, the author of the feuilleton, remains best known as the compiler of the popular and widely disseminated anthologies Buch der Sagen und Legenden jüdischer Vorzeit (Book of Sagas and Legends of the Jewish Past, 1842, with subsequent editions in 1845 and 1873), Fellmeiers Abende. Märchen und Geschichten aus grauer Vorzeit (Fellmeier’s Evenings. Tales and Stories from a Gray Past, 1856) and Sprichwörter und Redensarten deutsch-jüdischer Vorzeit (Proverbs and Sayings of the German-Jewish Past, 1860). In these collections, the latter two of which are directly referenced in his feuilleton,2 Tendlau dedicated sustained attention to Old Yiddish texts, which, as Aya Elyada has suggested, “he perceived as an integral part of Jewish tradition and collective Jewish memory.”3 Tendlau’s recovery of Glikl’s writings should be understood as part of his larger engagement with these texts, which did not merely reflect “an ‘archeological’ or ‘antiquarian’ interest in the past,” but rather, as Elyada has further argued with reference to Tendlau’s broader efforts and to those of other Jewish scholars in the nineteenth century, “was driven by the ambition […] to create a distinctive German-Jewish subculture, one that sought to link the Jewish past with the German present, and to enable nineteenth-century acculturated German Jews to retain their strong sense of belonging to the Jewish community and its heritage.”4

While Glikl’s untitled writings, composed between 1691 and 1719, are well known today, this is due to the philological and translational efforts of Tendlau, David Kaufmann, Bertha Pappenheim, Alfred Feilchenfeld, Marvin Lowenthal, and Chava Turniansky, among others.5 For over a century after Glikl’s death, her writings were only disseminated in manuscript form among her descendants—until, that is, Tendlau published excerpts from them in Der Israelit. In addition to demonstrating the importance of the feuilleton as a space for the recovery and circulation of forgotten texts, as well as for a popular kind of philology, Tendlau’s feuilleton highlights a number of more specific issues related to the belated evaluation of her writings, including two issues, both fascinating and frustrating, that are emphasized in the feuilleton’s title: genre and gender. In manuscript form, Glikl’s writings were untitled, whereas subsequent editors and translators have usually opted to label them “zikhroynes,” “Memoiren,” “memoirs,” or something of that sort. Tendlau opts for the related but distinct genre of the “Tagebuch” (diary), though he also draws attention to the fluidity of the source text, which “deals with the history of the author’s own family as well as with remarkable events near and far” and includes “heartfelt admonitions […] didactic stories, fables, sayings and the like.” Tendlau thus thematizes the difficulty or even impossibility of categorizing Glikl’s writings, which has remained a subject of debate among later scholars, editors, and translators.6 In certain respects, this categorical uncertainty befits the feuilleton, which has long been characterized by its generic lability, even as this particular example points up the bluntness and frequent lack of nuance in newspaper titles and headlines.

Furthermore, in his emphasis on the gender of the so-called diary’s author, Tendlau raises difficult questions about the role of women in the creation of “a distinctive German-Jewish subculture” in the nineteenth century and, in the process, reveals the gendered limits of his own scholarship and writing. While some later editors and translators, such as David Kaufmann and Bertha Pappenheim, embrace Glikl as a role model for Jewish women in modernity and as a productive resource for rethinking the place of women within Jewish society, Tendlau both underlines Glikl’s gender and marginalizes her because of it.7 Remarkably, he does not mention her name until about half-way through the feuilleton, when he refers to her as “Glück” or “Glücklich;” before and after, he refers to her merely as “Frau” (woman), “Verfasserin” (author), or “sie” (she). He arguably obscures, moreover, Glikl’s own character, motivations, and achievements—aside from her atypical education and reading habits—in favor of the manuscript’s condition and the history of her community and extended family, the latter reflecting his obvious interest in genealogical research.

Nevertheless, in line with his larger engagement with Old Yiddish texts (or texts, as he calls it, in “Jewish-German writing and vernacular”), Tendlau does emphasize Glikl’s language and writing style, in large part by including long quotations from the source text in a peculiar mixture of transcription, transliteration, and summary that recalls the hybrid language of his popular anthologies. In other words, he quotes, as he phrases it in the second part of the feuilleton, “zwar möglichst in ihrer eignen Sprache” (“as much as possible in her own language”).8 While Tendlau glosses many words and phrases, he also assumes the multilingualism of his audience and their at least basic familiarity with loshn-koydesh (the Hebrew and Aramaic component of Yiddish). In so doing, he seems to suggest that the linguistic textures of the “diary” are just as important as their content and just as captivating to German-Jewish readers in the latter half of the nineteenth century, as they grappled with the effects and implications of the sociocultural transformations of the Jewish community in the previous decades, marked not least by the linguistic shift from Yiddish to German. In my own translation of Tendlau’s feuilleton, I have tried to preserve the multilingualism of the original, while also inserting additional glosses of terms that may be unfamiliar to an English-language readership.

- See, for example, Jonathan M. Hess, Middlebrow Literature and the Making of German-Jewish Identity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010). For a more recent example that considers German-Jewish, as well as Yiddish, sources, see Sonia Gollance, It Could Lead to Dancing: Mixed-Sex Dancing and Jewish Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2021). ↩

- Sprichwörter is footnoted in the first part of the feuilleton, whereas Fellmeiers Abende is referenced in the third part: Tendlau, “Aus dem handschriftlichen Tagebuch einer Frau aus dem 17. Jahrhundert,” in Der Israelit 5, no. 8 (1864): 107. ↩

- Aya Elyada, “Bridges to a bygone Jewish past? Abraham Tendlau and the rewriting of Yiddish folktales in nineteenth-century Germany,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 16, no. 3 (2017): 422. ↩

- Ibid, 421. ↩

- Today, the most authoritative edition is that of Chava Turniansky. See Glikl: Zikhroynes 1691-1719, ed. Turniansky (Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2006), which is accompanied by her Hebrew translation of the Yiddish text. See also the English translation: Glikl: Memoirs 1691-1719, ed. Turniansky, trans. Sara Friedman (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2019). ↩

- See, for example, Chava Turniansky, “Tsu vosr literarishn zshaner gehert Glikl Hamels shafung?,” Proceedings of the Eleventh World Congress of Jewish Studies, Section C, Vol. 3 (Jerusalem 1994): 283-290. ↩

- For more on Kaufmann and Pappenheim, see, for example, Elizabeth Loentz, Let Me Continue to Speak: Bertha Pappenheim as Author and Activist (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2007); Mirjam Thulin, Kaufmanns Nachrichtendienst. Ein jüdisches Gelehrtennetzwerk im 19. Jahrhundert (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2012); Louise Hecht, “Übersetzungen jüdischer Tradition. Bertha Pappenheims religiös-feministische Schriften,” Hofmannsthal-Jahrbuch. Zur europäischen Moderne 20 (2012): 288-344; and Matthew Johnson, “Glikl’s Circulation: Editing, Translating, and Value,” in Michael Gamper, Jutta Müller-Tamm, David Wachter, and Jasmin Wrobel (eds.), Der Wert der literarischen Zirkulation (Berlin: J. B. Metzler, 2023), 291-311. ↩

- Tendlau, “Aus dem handschriftlichen Tagebuch einer Frau aus dem 17. Jahrhundert,” in Der Israelit 5, no. 7 (1864): 89. ↩