Explore Feuilletons

Demons on the Jewish Street

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Hersh Dovid Nomberg. “Demons on the Jewish Street,” 1914. Translated by Samuel Glauber

Things are happening on Nalewki Street: demons dance about, dybbuks and malevolent spirits, a “water-medium” follows with wonder; thousands of Jews gather in a clamorous courtyard and wait for a dybbuk; a young girl from the provinces through whom the dybbuk speaks in a man’s voice. The maggid of the courtyard synagogue will expel him.

The crowd is frightened. There is some danger involved, for when a dybbuk flies out of someone, it can immediately enter into another person. Young people (one of whom I recently saw for the first time at a gathering) hold on to their gartels. A seemingly respectable Jew, a leather merchant from Franciszkańska Street, shares that he saw the dybbuk with his own eyes. She opened her mouth and “it spoke through her.”

Read Full

Another person relates that the dybbuk will not come out now. It is actually in a tree […] on whose branches fruit grow, and over each fruit a different blessing must be said.

There is a racket outside and Nalewki is filled with noise. Carts, piled up high, are dragged across the cobblestones; buyers and sellers make investments, Circassians, Mountain Jews1—everyone does business here. They say that Nalewki does good business; they say that the season is a good one, and that there is a tremendous influx from the most distant markets; they say that Nalewki is one of the most important centers of global commerce, the go-between for Europe and the Far East. Not true! Nalewki exorcizes dybbuks, demons dance on Nalewki!

A deep abyss of the darkest, most foolish superstitions sleeps in our midst. No one knows of it, no one speaks of it, until one day someone, a girl, comes along, the abyss emerges, and we are made aware of its existence.

And it transpires without fear. No! There is no fear, only a shame of oneself. We remain sitting with the pen in hand, stunned and disconcerted. How do we address the public? What do we tell them? Hebrew or German in the Haifa Technicum? The Zionists and Prof. Hermann Cohen? Immigration questions? Self-awareness, human will, national consciousness? Do we appeal to the “Jewish public”? We feel as if someone has hollowed out the words until they are left with no content. We are borne through a wilderness, demons dance around, spirits look out from the cracks in the jagged rocks, and a malevolent satyr makes strange contortions, dancing on all fours, laughing at us—us and our whole lexicon of European-humanistic words, us and all of our notions, us and all of our desires, our propositions, our ethics and our counsel.

A sense of alienation assails us.

We stand on Nalewki street, our economic bastion. In a great European world-city, the largest Jewish center of Europe. Here it is, our “authoritative public.” When we wish to build a Jewish land, we appeal to here; when we wish to develop a culture, our eyes turn here; when we wish to create a better theater, we call to Nalewki; Ussishkin insults our greatest poet—Nalewki, let your word be heard!2

But in the middle a malevolent imp jumps in with its horns and shouts the word “demons,” and we look around to see what happened: 90% of our “governing public” who should be building up the Jewish land, creating a Jewish culture, etc., run after evil marvels and chase dybbuks.

And the words congeal in our mouth.

For there is nothing to be done with people who hawk demons and propagate dybbuks. As long as the person does not feel the firm ground of our earth under his feet, you will not make him a citizen of our earth. You must start him off with the ABCs, you must first expel the demons and spirits from his head, so that you could begin speaking with him in a civil language about civil matters.

We were a little late. The Yiddish press came after the Hebrew press and assumed its traditions. We had reached the moment in Hebrew literature when the so-called “Haskalah period” was over. The war against darkness had become a disgrace and a mockery. We thought the work was finished. Speaking out against the foolish superstitious beliefs in demons, spirits, and dybbuks, as the first maskilim did, would be to make a fool of oneself. “The experience which exists no more in life becomes an object of poetry, pride, and art,” says Spencer.3 We did as much with our old superstitions; reckoning that they no longer really exist, they were rendered into verse in artistic works. But we suddenly discover that demons dance about the Jewish street, much as they did 60–70 years ago, and we realize our tremendous miscalculation:

The Yiddish press (and Yiddish literature. Yes, it too!) did not need to, nor could it, simply start up from where the Hebrew press left off. The latter spoke to a limited circle of readers, to a few tens of thousands of people of high worth. And when the Haskalah struggle was possibly already finished, here it still needed to begin, here among the hundreds of thousands whom the labor of a generation of maskilim did not reach.

We were not prepared for the task.

And here we have the results.

For long enough now the word “demons” has been let loose in the Jewish street, in the most modern city, where such a great Jewish collective lives, and tens of thousands believe, and tens of thousands run to see it with their own eyes; it is enough already, that a mentally-ill girl, or a trickster out to make a living, should cry out in a strange voice and Nalewki becomes black with people, and thousands stand for hours awaiting miracles.

We have stared into the abyss of darkness; due to an accidental tremor, it revealed itself to us in its considerable proportions. It is an open field for malicious people to use superstitions for their own purposes. It pays well to speculate on the stupidity of the people and to play on their dark fantasies.

The abyss is perilous and dark, the way out is very slippery.

Halt, coachman!

You’re driving off a cliff.

- The author uses the term “gortses,” which is, most likely, a reference to Jews from the Caucasus, which in Russian are called “Gorskie Yevrei.” ↩

- The Zionist leader Menahem Ussishkin (1863–1941) was a fierce proponent of a monolinguistic Hebrew culture in Palestine in opposition to all other languages, in particular Yiddish. ↩

- This allusion might refer to Edmund Spencer (1552-1599) or Herbert Spencer (1820-1903). ↩

Commentary

Hersh Dovid Nomberg. “Demons on the Jewish Street,” 1914. Commentary by Samuel Glauber

This feuilleton was published on March 6, 1914, by Hersh Dovid Nomberg (1876–1927) in the Warsaw Yiddish daily newspaper Haynt. Nomberg’s feuilleton appeared amidst a wave of public interest among Warsaw Jews in demons, dybbuks, and mediums set off by a report published in early February in Der moment—Haynt’s crosstown rival—that a tenement home in the Jewish quarter of the city was haunted by demons. Chaos ensued, and for the next month the city was seized by rumors of hauntings as nearly fifty articles appeared in the city’s Yiddish newspapers covering the affair. The events reached a crescendo on the night of March 3, as thousands of Jews packed into the courtyard at 35 Nalewki Street, the beating heart of Jewish Warsaw, to witness the exorcism of a dybbuk from the body of a young woman. “Demons on the Jewish Street,” which opens with a vivid description of the frenzied crowd from the writer’s perspective, turns a critical eye to the preoccupation with demons and dybbuks that had overrun Warsaw and the role of the Yiddish press in its promulgation.

Read Full

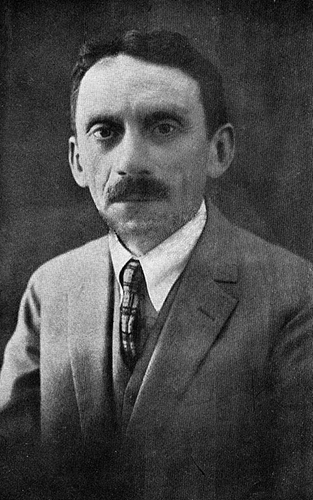

Hersh Dovid Nomberg (1876–1927) was a leading Hebrew and Yiddish writer, playwright, and social activist in early-twentieth-century Warsaw. Fiercely committed to the development of a modern Jewish culture in the Yiddish language, it was he who coined the term Yiddishism. To that end, he advocated for folkism (another term that he devised), the Jewish political ideology that argued for national cultural autonomy in the Diaspora, briefly serving as a party delegate in the Sejm, the Polish parliament.

The text centers around Nalewki Street, the center of Jewish commerce in Warsaw. More than just a street, Nalewki with its teeming courtyards was the physical locus of the Jewish body politic in the city, then the largest Jewish community in Europe. Nomberg’s feuilleton presents two opposing images from Nalewki—the bustling commercial activity on the street, emblematic of Jewish collective socio-economic development, and the sordid scene that played out in the inner courtyard of Nalewki 35, where thousands thronged to witness a dybbuk exorcism. For Nomberg, much like for the generations of maskilim who preceded him, the task of ushering the Jewish masses of Eastern Europe into the modern world began with the excision of any vestigial beliefs in demons, dybbuks, and the like. The contrast between the “exterior” Nalewki, hub of Jewish economic and cultural life, and the “interior” Nalewki, where Jews still grant credence to spirit possession, illustrates the yawning gap between Nomberg’s envisioned modern Yiddish-speaking Jewish collective, and how this collective revealed itself to be in actuality. Confronted with the sight of Jews gathering for a dybbuk exorcism in Warsaw, the supposed vanguard of Jewish modernity in Eastern Europe, his pen runs dry. “There is nothing to be done,” he laments, “with people who hawk demons and propagate dybbuks.”

Nomberg then turns his sights on the nascent Yiddish press, which began to develop rapidly in Eastern Europe from around 1905. The Yiddish press, he writes, made the mistake of assuming the same standard of cultural development as the veteran Hebrew press, whose newspapers reached a small, highly educated readership. While Hebrew literature had arrived at a “post-Haskalah” stage in which demons and dybbuks, now safely relegated to the realm of fantasy, could be reapproached as the subjects of artistic creation, the hundreds of thousands of readers of the Yiddish press, never having come under the edifying influence of the Haskalah, still regarded the phenomena as real. Der moment, in reporting on a haunted house several weeks earlier, had unwittingly unleashed “a deep abyss of the darkest, most foolish superstitions” that culminated in the Nalewki Street exorcism. However long the masses continued to believe in demons and dybbuks, it was not yet safe to engage with the latter in anything other than a critical light.1

- It is interesting to note that Nomberg penned his feuilleton only a few short years before the 1920 Yiddish-language debut of S. An-sky’s landmark play The Dybbuk, an inspired work of fiction whose remarkable success, Yoram Bilu argues, marked the transformation of the dybbuk from real-world phenomenon to stage performance. See Yoram Bilu, “The Return of the Dybbuk: Between Ritual Healing and Stage Performance,” The Drama Review 64, no. 3 (2020): 33–51. ↩

Further Reading:

- “Nomberg, Hersh Dovid.” YIVO Encyclopedia. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Nomberg_Hersh_Dovid