Explore Feuilletons

Light and Joy

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Shalom Bekache, “Light and Joy,” 1891. Translated by Avner Ofrath

Peoples all around the world hold celebrations for their great minds when they turn seventy, eighty, or hundred years old. Even after such figures pass away, one always commemorates and celebrates their birth dates.

Read Full

For instance, there was a huge festivity for the great poet of France Victor Hugo when he turned eighty years old.1 There was also a celebration when the writer Chevreuil reached a hundred years.2 Furthermore, there was a huge celebration in France last year, since that was the hundredth anniversary of the birth of the writer Lamartine.

Beyond writers, there are celebrations for all important3 dates of their history, which they always commemorate with great joy. Thus, in all the countries of the French, there are commemorations of the revolution that took place in the year 1789.4 And next year there will be a huge celebration in America, because it is the 400th anniversary since Christopher Columbus5 discovered this new world (America).6 And such festivities are also common beyond the nations mentioned here. Indeed, even our brethren, the Jews all over Europe, hold a great festivity for their great minds (each in his own country) whenever they turn seventy, eighty, or a hundred years old.

Such was7 the festivity carried out all over the world when Sir Moses Montefiore turned a hundred years old.8 Each and every year there are celebrations of this kind. Last month, the Jews of Vienna in Austria held a great celebration because their rabbi Aharon Jellinek turned seventy. And the same in Paris, because the rabbi Shneur Zaks, who is known around the world for the precious exegeses that he wrote, turned seventy-five.9 And so was done for the rabbi of Copenhagen when he accomplished ninety years. Even in Romania, the land of troubles and exile, our brethren hold many festivities these days for the great rabbi Hillel Kahana, who began his 71st year (may God prolong his good and pleasant days).

Indeed, next year there shall be a great celebration amongst the Jews. This year will mark a thousand years since the birth of the great rabbi Saadia Gaon. His entire writing will be printed anew. Rabbi Joseph Derenbourg from Paris will preside over the festivity in France and he is the one who initiated this cause. Beyond this celebration, they intend to commemorate next year the exile from Spain, which occurred four hundred years ago (1492) in the days of Ferdinand V the Evil and his cursed wife Isabel. Rabbi Don Isaac Abarbanel is one of the Jews who were expelled that year.

All that is mentioned here is only to remind our brethren: Go out and learn. This year marks five hundred years since our rabbis Isaac ben Sheshet and Simeon ben Zemah Duran came to Algiers.10 Five centuries since their light of the Torah has shone on us. For the Torah represents light, as the verse states.11 There is no better or more suitable time for a Jewish celebration than the occasion of this year.

Indeed, the arrival of these two great rabbis in Algiers is considered to be the day when our country was born. For what was Algiers before the sun of these two rabbis had shone on her? […] They are the ones who elevated her standing and gave her great fame in the entire world […] There is no other time for a great celebration than this year, marking five centuries since the Torah came to Algiers, since the Tree of Life has been planted in our country – the Tree of Life which is the Torah itself, which gives life to everyone who reads it and to this day bears wonderful fruits.

For this reason, we ask our brethren, and especially the Grand Rabbis [of Algeria] and the members of the [Algerian] Consistory to consider this, so that we can have a great celebration for the two dear rabbis, famous around the world,12 so that their great merit, the merit of the Torah which they brought to us in Algiers shall last forever.

- The word “Poet” appears both in Arabic and in Hebrew. ↩

- Unclear name. May refer to Chateaubriand or Chevalier, or possibly Eugene Chevreul, a French scientist. ↩

- The word used in the original is mshʿūnīn, which in standard Arabic can mean hideous, ugly, abominable, etc. It is unlikely that this was the author’s intention, hence the translation here. ↩

- The phrase “all the countries of the French” denotes territories beyond France itself. ↩

- In the original: transliteration of French pronunciation and spelling for ‘Christophe Colombe.’ ↩

- In the original: transliteration of French pronunciation and spelling: Amérique. ↩

- Exact literal meaning of the phrase unclear: אשכון מא סמאעש. ↩

- The text features the habitual Hebrew designation: “Ha-sar Moshe Montefiore” ↩

- Known in English as Senior Sachs. ↩

- In the original “rabbis” appear as “Admor” (אדמו”ר). ↩

- Here comes a repetition in Hebrew: ותורה אור. ↩

- “Fi arb‘a pinot ha-‘olam” (פי ארבע פינות העולם). ↩

Commentary

Shalom Bekache, “Light and Joy,” 1891. Commentary by Avner Ofrath

Know thyself, says rabbi, journalist, and publisher Shalom Bekache (1848-1927) to his reader in this feuilleton – an appeal to develop a decidedly Algerian-Jewish historical consciousness. Though not defined as such, the text translated here – like many other of Bekache’s articles – presents the main characteristics of the European tradition of the feuilleton, which clearly influenced him: a relatively long text that discusses matters of societal and cultural interest, but in a more abstract manner than day-to-day news. Indeed, Bekache’s journal featured a spectrum of topics and a level of sophistication that were uncommon in the landscape of the Algerian Jewish press. Within the first six weeks of his journal’s publication in 1891, he discussed gender relations, language and education, anti-Semitism in Europe, and the controversy between Rabbinic and Karaite Judaism.

Read Full

At first glance, the core argument may seem rather trivial: Jews in Algeria should adopt the custom of ‘peoples around the world’ to mark important historical anniversaries. But behind it stands a more fundamental argument about Jewish history and its role in the contemporary world. Bekache calls on his readers and on the Jewish community in Algiers to commemorate the anniversary of the arrival of the Geonim Isaac ben Sheshet and Simeon ben Zemah Duran in Algiers in 1391. He argues that their arrival was a key historical moment, as he writes: “For what was Algiers before the sun of these two rabbis shone on her? […] They are the ones who elevated her standing and gave her great fame in the entire world.”

Much like French commentators on Algerian Jewish life since the 1830s – Jews and non-Jews alike – Bekache adopts a view of Algerian history as one marked by binaries: darkness vs. enlightenment, ignorance vs. learning, stagnation vs. progress. Yet for Bekache, this history is almost entirely untouched by the timeline of French history. Unlike most other texts published in the Algerian-Jewish vernacular in the late 19th century, the French milestone years of 1789, 1830, or 1870 play no role at all. Rather, it is the rise and demise of Jewish scholarship in Spain and the Mediterranean diaspora in the aftermath of the persecution of the Catholic Reconquista that are depicted here as the origin of a renaissance of Jewish life in Algeria.

To whom is this text addressed? Bekache writes to the common Jewish reader, no doubt, but also to the chief rabbis and the consistories of Algeria – the councils founded by France in the 1840s to oversee the reshaping of Jewish education, family structures, and religious life to follow the French model. It is also worth noting that Bekache’s tone is not entirely neutral. “Go out and learn” about the arrival of the two Geonim, he tells the consistory members, borrowing an expression from the Passover Haggadah – a key Jewish text that commemorates historical events – and implying that Algerian Jewish leaders lack knowledge of their own history.

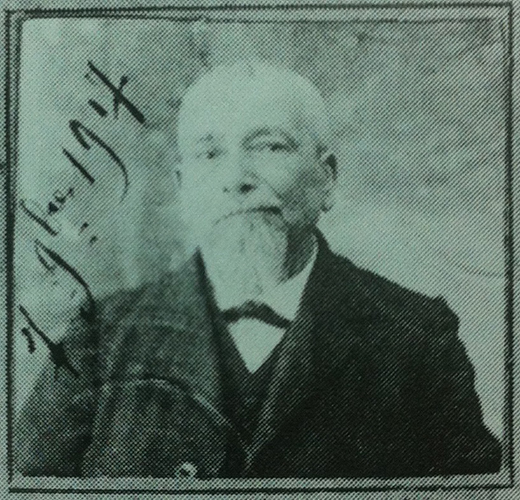

It is not coincidental that Bekache adopted this critical outsider’s tone in his feuilleton. A native of Mumbai who was ordained as rabbi in Safed, Bekache settled in Algiers in 1878. He was in a unique position to observe a society undergoing rapid changes, thanks to his migration and strong ties throughout the Jewish world, his command of Hebrew, and the fact that he settled in in Algiers only a few years after the bestowal of French citizenship on Algerian Jews with the 1870 Crémieux Decree. Within a few years of his arrival in Algiers, he founded a printing press, published numerous books, and in 1891 launched Beit Yisrael, a weekly journal written in the Judeo-Arabic vernacular of local Jewry, and in which this feuilleton was published.

Like most maskilim – proponents of the Haskalah – Bekache did not reject European influence altogether and his articles in Beit Yisrael include repeated references to France as a source of civilization and progress. Yet he clearly rejected the French colonial imperative of assimilation, insisting on writing in Judeo-Arabic, promoting the knowledge of Hebrew, and finding a decidedly Jewish way to modernity.’ In this feuilleton, Bekache turns his attention to Algerian Jewish history by infusing it with practices inspired by French culture. In doing so, he offers a model for modern Jewish identity that draws on modern European thought, the Jewish Enlightenment movement (Haskalah), and local traditions.

Further Reading:

- Avraham Hatal, “Sifre rabi Shalom Bekach, ish haskalah, madpis ve-mo”s be-Algir,” Ale-sefer 2, 1976: 219-228.

- Avner Ofrath, 'We Shall Become French': Reconsidering Algerian Jews' Citizenship, c. 1860–1900, French History 35:2 (2021): 243–265.