Explore Feuilletons

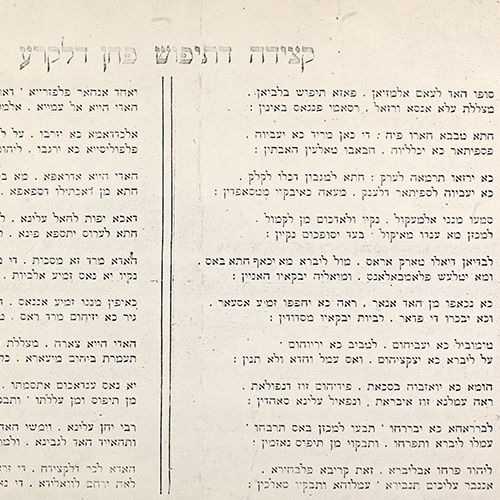

Qasida of an Epidemic of Typhoid Fever

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Place issued

Author

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

ayin-bet dalet-bet, “Qasida of an Epidemic of Typhoid Fever, in Verse of the Tinea capitis,” 194?. Translated by Academic Language Experts team, Yom Tov Gindi and Joshua Amaru

Observe this good year, in which the typhoid fever broke out Erupting against women and men, leaving its imprint on humankind. Even the doctors were amazed; he who fell ill was taken And placed in the hospital, friends coming up and down. Hoping the unfortunate one would be drenched in sweat until his discomfort would ease, They took him to a neck clinic; with him would they remain. Hear from me a word of reproach. Cleanse your children of lice. The ruler will have nothing to say after he sees you clean. It begins with headaches; the inoculated will have nothing to fear. They won’t be loaded into ambulances; their households will remain at ease. We fear this flame; they should thin out their hair And burn incense at home, keeping their homes sealed. A car will take them to a doctor who will see them. About an injection, he asks them: Did you do one or two? And quietly they reply, clutching two test tubes. Look, we received two injections, as the test tubes attest. Yesterday the thing was done; heed the ruler so that you will make gains. Take an injection and you’ll be happy and calm as typhoid fever rampages. Jews, take pleasure in that injection, which came from nearby from the direction of the sea. I warn you with moral counsel: Do it and stay healthy. Then one day at dawn, policemen came to town. This is the blinding blow, to the Jewish quarter they turn. The workers will rush, on bicycles will they flee. For the police have come to inspect; to them they return on sundry excuses. This is the blow; neither girl nor matron remained. Until humiliated and they returned against their will. Soon it will all blow over, even meals will irk us. The groom will yet laugh at us, the young men on whom we rely. It’s a quiet illness; the careless die fast. People, clean all your houses, and typhoid fever will you outlast. Everyone fears it, from Casablanca and Marrakech. The illness of the head will come upon them, will find them prostrate at home. This woe has overtaken the young men. It has heaped reproaches upon them, all of them together with the elders. People, isolate yourselves in place; heed the doctors and endure. From typhoid fever and its depredations will you be forever inured. May God pity us so that the plague be gone, Cleanse us of this vexation and let the ill rebound. Thus ends the qasida to what occurred in Casablanca. May God have mercy on the mother (of the author), Hark, all ye in attendance.

Commentary

ayin-bet dalet-bet, “Qasida of an Epidemic of Typhoid Fever,” 194?. Commentary by David Guedj, translated by Academic Language Experts team, Joshua Amaru

The feuilleton “Qasida of an Epidemic of Typhoid Fever” was published on a single folio, apparently in Casablanca and by all appearances in the 1940s. Its anonymous author signed his name with the initials ayin-bet dalet-bet. Written in the form of a qasida, a poetic genre originating in the pre-Islamic era in the Arabian Peninsula, it describes an epidemic of typhoid fever that was spreading in Morocco. The writer describes the doctors’ astonishment in the face of the epidemic and reports the plight of those seriously ill in the hospital. He urges his readers to maintain hygiene, to shelter in place, and to accept inoculation to fend off the illness. At the end, he pleads with God to have mercy on the community so that the plague will disappear and the ill will recover.

Read Full

This folio was one of hundreds of similar pamphlets that were published at this time in Morocco. These were not the feuilletons that appeared in the Judeo-Arabic press but rather individual sheets of paper that writers produced, printed, and published on their own. This phenomenon is not unique to Morocco; it has parallels in Jewish communities in North Africa at that time. Loose folios were also common in Jewish communities in Europe, but there the phenomenon waned as the Jewish press evolved.

I propose that these stand-alone folio publications be attributed to the feuilleton genre because their characteristics overlap those of feuilletons. The word feuilleton in French means “leaf” or “folio” because the first feuilletons were printed on a separate page attached to the newspaper; only later did they appear inside the newspaper, and even then, in a separate section. The stand-alone folios were produced by writers who printed and distributed them independently and in bookstores. In the first half of the twentieth century, most Jewish newspapers in Morocco were published in French; few appeared in Judeo-Arabic due to difficulties that the colonial authorities placed in their path. One may regard the individual folios as manifestations of resistance and of a cultural product that circumvented the government’s oversight. Fear of the authorities prompted some writers to publish their works anonymously or to identify themselves only by their initials.

The folios addressed themselves to the public at large, comprised of readers who were fluent in Judeo-Arabic. Since relatively few North African Jews read Judeo-Arabic, the folios were not only read by individuals but also read aloud to groups of listeners. The language used was colloquial Judeo-Arabic rendered in Hebrew characters and not literary Arabic, in which the Jews of the Maghreb were not proficient. Until these single folios were printed, such texts were composed and preserved as part of an oral culture or within a culture of manuscripts that were now widely printed and distributed for the first time.

All the works were written in a maqam form that presents diverse poetic-literary works in a combination of rhymed prose with rhetorical flair and metered poetry. The singular style of the poetic works that were published on these single folios is unsurprising because the predominant literary endeavor in North Africa, among Muslims and Jews, was poetry in all of its forms. This poetry, passed on by oral tradition, was written down once printing had become widely available in Morocco.

The contents of the folios are highly diverse. In some, the writers express an opinion about current affairs or use the literary genre as an instrument of direct or satirical criticism. Some works recount a fictional tale and others a historical event. Some of the works resemble a lamentation or eulogy, describing someone who has died, others deal with issues of modern society. In the feuilleton presented here, as stated, the writer describes an epidemic of typhoid fever in Morocco.

Further Reading:

- Yosef Tobi and Tsivia Tobi, Judeo-Arabic Literature in Tunisia, 1850-1950 (Detroit, 2014).