Explore Feuilletons

On the One Hand, and on the Other

Item sets

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Translator

Contributor

Keywords

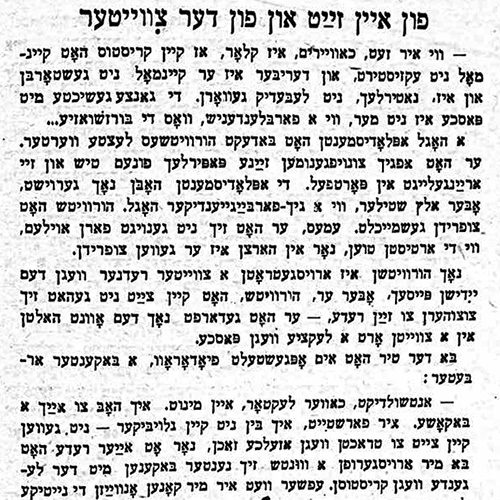

Original Text

Translation

Oskar Strelits, “On the One Hand, and on the Other,” 1929. Translated by Daniel Kennedy

“So as you see, comrades, it is clear that Jesus never existed. And therefore he never died, and so, it stands to reason that he was never resurrected. The whole story of Easter is nothing more than a delusion, which the bourgeoisie . . .”

Hurvitsh’s last words were drowned out by a hail of applause. He quickly gathered his papers from the table and put them into his briefcase. The applause continued, but gradually grew quieter, like a quickly passing hail shower. Hurvitsh smiled contentedly. True, he did not bow before the audience like an actor, but in his heart he was satisfied.

Read Full

Hurvitsh was followed by a second speaker, lecturing on Jewish Passover, but Hurvitsh did not have time to stay and listen; he had a second lecture to give that same evening, also on the topic of Easter.

At the door he was stopped by Fiodorov, a worker of his acquaintance:

“Excuse me, comrade speaker, one moment please. I have a request for you. I’m not a religious man, you understand, never had time to think about that sort of thing, but your speech made me want to get to know the legend of Jesus a little better. Perhaps you could point me in the direction of the necessary reading materials?”

Hurvitsh considered for a moment and as he was in a hurry he soon found a way out:

“Tell you what, come to my home some evening and I’ll show you the literature and maybe let you borrow a few books.”

Hurvitsh hurried through the streets to the club where he was due to speak again. Spring was making itself felt. The gutters did not freeze over even at night. Up above, a pure starry sky twinkled and mild, fragrant breezes blew. His winter coat began to feel heavy.

Hurvitsh let out a chest-full of air. He suddenly felt a playful urge, and he remembered his youth. A young blonde girl, unbuttoning her coat, walked past him.

He arrived home late in the evening, pleasantly fatigued. His second lecture had been an even greater success. With razor-sharp wit he had ridiculed religion and the petit-bourgeoisie. The audience laughed and gave him a warm round of applause.

At home he was pleasantly surprised to see that everything had been cleaned and tidied. The evening windows shone brightly, their freshly-washed panes reflecting light back into the room.

Bobeshi (grandmother) entered from the other room carrying a candle searching for something on the windowsill.

“What are you looking for, Bobeshi?”

She searched the windowsill once again with her failing eyes, giving it another wipe of the feather duster.

“Did you forget that today’s the day Jews clean their homes of khomets?” “Khomets? Ha ha, I’d completely forgotten.”

At that point Hurvitsh remembered that this year marked fifteen years since he’d married his wife Fania. He remembered well how on the eve of Passover, to spite several bourgeois relations, they had married in a small town nearby. Even back then he’d held no store with marriage ceremonies, but for his parents’ sake they had hastily set up a wedding canopy, followed by a soiree for close friends.

After the wedding he attended seder at his father’s house. He did not believe in the Exodus from Egypt—but why aggravate his parents? He would not change their ways, and he himself would become no less of a revolutionary if he failed to maintain an unbowed sectarian line with members of the older generation.

After the seder he met up with Fania. It was an evening just like this one. A cleanly-swept, starry sky. The blood simmered, yearning for something. They talked long that night about the touching naivety of the old ways, about the wonderful folklore that lay in the Passover rituals, in the seder meals . . .

His wife entered the room. She was still a charming brunette, an agreeable wife, if somewhat careless and slovenly. He told her that his bobeshi had searched the house for khomets, and waited for a response.

“You know she wants us to be at home tomorrow evening, no less? In her old age, she says, she wants to spend the first seder with family. Will you be there?”

Hurvitsh thought for a moment—he had no meetings the next day, nor any speaking engagements. There was only a regional party gathering which he was not obliged to attend. In truth, he could have an evening to himself for once.

“Yes, I’ll be home tomorrow.” “I’ll invite a few other friends too,” his wife added.

* * *

Whether it was Bobeshi’s or his wife’s doing, Hurvitsh saw that there was wine on the table. Fania whipped up a fried dish, which resembled latkes made of eggs. It was made of soaked matzo-meal.

Bobeshi read from the Haggadah. Her glasses hung on the end of her bluish nose, and her eyes were fixed on the text. Hurvitsh and Fania sat at the table, seemingly perusing a newspaper, but quietly, so as not to disturb Bobeshi in reciting the Haggadah.

There was a knock on the door. Fania went to open it: some friends had arrived who worked with Hurvitsh at the trust. They brought the spring evening in with them and a brief racket upon first entering. The women conversed with Fania about where they would go for summer vacation.

“This year it will be hard to arrange a foreign trip. We’ll probably have to go to Kislovodsk.” “Yes,” one of them let out a long sigh. “It’s getting harder to go abroad, and in general . . .”

Bobeshi finally shut the Haggadah. The conversation became more animated.

“Have you heard the latest joke?”

They took their places at the table. Fania had put on a short apron, which seemed to hug her figure, making her slimmer. One of the guests examined her and said:

“Fanitshka! I swear you look younger today.”

Fania smiled and fetched her fried matzo dish and placed it on the table. The wine sparkled red in the glass tumblers. Bobeshi took a sip of the knaidel soup and crumbled some matzo crumbs into it.

There was another knock on the door. Fania went to open it and soon returned accompanied by Fiodorov.

“Ah, Comrade Fiodorov,” said Hurvitsh. “You’ve come for the books I imagine, about Chistianity?” Then to the guests he said, “One moment, excuse me.”

He went to the bookshelves and looked through the books. Awkwardly, Fiodorov observed the guests and the whole table. Fania noticed.

“Tonight is something of a family holiday for us,” she explained.

Bobeshi lifted her head and peered at Fiodorov through her glasses. Then she sought out a large piece of matzo and brought it to him.

“Try this, Grazhdanin,1 a little Jewish matzo,” she said, slipping some into his hand. Fiodorov stood there with the matzo in his hand, unsure what to do.

Hurvitsh finally found the desired book and brought it to Fiodorov but seeing the piece of matzo in his hand he became flustered and, avoiding eye-contact, he began to wipe his American horn-rimmed glasses. The room went quiet.

“Well, Comrade Hurvitsh, it seems that the Jewish Jesus existed after all,” Fiodorov said.

Hurvitsh wiped his glasses all the more frantically.

- Russian: citizen. ↩

Commentary

Oskar Strelits, “On the One Hand, and on the Other,” 1929. Commentary by Mikhail Krutikov

Born in 1892 in Kovno, Russian Empire (today Kaunas in Lithuania), Oskar Strelits was, like many Jewish authors of that age, a politically radical autodidact. After the October Revolution he settled in Moscow where he attended a university and worked at the editorial office of the central Yiddish Communist daily Der Emes (Truth). In the 1920s he also served for some time as the editor of a Yiddish newspaper in Kalinindorf, a Jewish agricultural colony in Ukraine. He published three books of short prose, among them a collection of his feuilletons, Aropgerisene maskes (Torn-off Masks, 1932).

Read Full

In the Soviet Union, the feuilleton was a popular newspaper genre. It could be a satiric piece mildly criticizing certain aspects of Soviet life, or militant political satire aimed at foreign or domestic personalities who were at that moment considered enemies by the Soviet regime. “On the One Side, and on the Other” by Oskar Strelits combines both features. It is set during the anti-religious campaign that was launched by the Communist Party in the late 1920s. The campaign combined persuasion – such as public lectures – with more violent actions such as closure of religious buildings, confiscation and destruction of property of religious organizations, imprisonment and execution of clergy.

The situation described by Strelits was part of the annual “anti-Easter campaign” aimed at preventing people from observing the holiday. The irony of that situation is the fact that the propagandist, who tries to convince his presumably Christian audience that Jesus had never existed and therefore could not have been crucified and resurrected, is Jewish. In reality, the active participation of Jewish communists in anti-Christian campaigns did create a great deal of resentment among the general population and led to a rise of antisemitism, which at that time was considered a crime punishable by prison. Strelits exposes the two-facedness of the professional atheist Hurvitsh who eagerly condemns Christianity but has no qualms about participating in the Jewish Passover ritual with his family and friends. His hypocrisy is masterfully revealed in the punchline, pronounced by the non-Jewish worker: “Well, Comrade Hurvitsh, it seems that the Jewish Jesus existed after all.” Had this piece been published in Russian, it might have been perceived as antisemitic, but in Yiddish such satire was permissible.

This feuilleton is dated April 1929, a year known in Soviet history as “The Year of the Great Break.” Having crushed the Trotskyist opposition, Stalin launched an aggressive policy of collectivization and industrialization which changed the life of every Soviet citizen. The characters in Strelits’s feuilleton already feel the coming changes. They nostalgically recall the period of the New Economic Policy which allowed a certain degree of economic and ideological liberty. This sentiment exposes them as “petty-bourgeois elements,” to use the Soviet parlance of that age, who will be soon declared the main “enemies of the people.”

Most of Jewish communists - members of the Evsektsiia (Jewish Sections of the Communist Party) - were sincerely committed to the cause. Their ideological leader was Moyshe Litvakov (1875/80-1939), a shrewd literary critic and the editor of Der Emes, who executed the ideological control over Yiddish culture. In the preface to Aropgerisene maskes Litvakov formulated the task of the feuilleton in Soviet literature: “Literature is an ideological weapon in class struggle […] and feuilleton is in this sense a sort a light cavalry which is meant to strike swift and deep” (p. 3). Litvakov valued Strelits’s feuilletons for their psychological subtlety and “lyricism” but found his satire insufficiently aggressive in its attack at class enemies (p. 13). Like many of their fellow communists, both Litvakov and Strelits were themselves declared class enemies and perished in the Stalinist purges of the late 1930s.