Explore Feuilletons

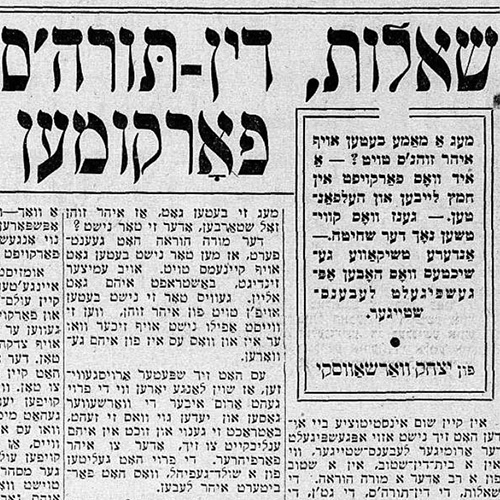

Religious Questions, Rulings, Divorces, and Weddings from a Rabbinical Court in Poland

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Copyright holder

URI

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Isaac Bashevis Singer, “Religious Questions, Rulings, Divorces, and Weddings from a Rabbinical Court in Poland,” 1944. Translated by David Stromberg

Can a mother pray for her son’s death? – A man who sells lions and elephants as leavening. – Geese that shriek after slaughter. – Other odd stories that reflect an entire way of life.

No Jewish institution better reflected neighborhood life than the rabbinical court – whether in the house of a rabbi or any other religious adviser. The ritual questions and rulings, the divorces and the weddings that passed through the rabbinical court offered a picture of everything that was unique and remarkable about Jewish life. Many of these questions and rulings could serve as themes for writers both of novels and of literary sketches. The writer of these very lines had the pleasure of observing what takes place in a rabbinical courtroom in Warsaw for many years.

Read Full

Once, the door opened and into the room walked an old woman. It was clear she’d been beautiful in her youth.

“What good news do you bring?” asked the religious adviser. “Rabbi, I have a religious question,” the woman said with hesitation.. “So ask.” “It’s not a regular question . . . I’m afraid to let the words out.” “Don’t be ashamed and don’t be afraid. Just speak the truth!” “Rabbi, can a mother pray for her son to die?” the woman asked. “Speak clearly!” said the adviser, getting angry.

The woman told the following story: she’d been seduced when she was young, and given birth to an illegitimate child, a son. She’d abandoned the child. She had no idea, to this day, what happened to him. All she knew was that the child had been brought to a Polish orphanage where they raised abandoned children. She was sure they raised the boy as a goy – and an anti-semite. Not long ago, as she walked down the street, she saw a Polish firefighter hitting a Jewish man. All at once, it seemed to her that the firefighter was her son. She was almost certain. He looked both like her, and like the man who’d seduced her. She was so flustered that, since it happened, she couldn’t sleep at night. She spent some time looking for the firefighter, but couldn’t find him. She has only one wish now – that the antisemite should drop dead. She refuses to bring forth progeny that abuses Jews. She’s come to ask: Is she allowed to ask God for her son’s death – or should she not?

The adviser answered that one should never ask God for anyone’s death. When people sin, their punishment comes from God alone. She should certainly not ask for her son’s death, since she doesn’t actually know where he is or what happened to him.

It later turned out that the woman had for many years walked the streets of Warsaw and thought the exact same thing every time she saw a Polish man – in whom she looked for any possible resemblance either to her or to the man who’d seduced her. The woman suffered from feelings of guilt that had embittered her life.

“What should I do, Rabbi?” she asked, wringing her hands. “I will be the bearer of evildoers, antisemites, Jew-haters. I’ll never be able to rest – not even in my grave. The more time passes, the more grandchildren I’ll have – the evil kind. What should I do? Where should I go? Where should I run?”

The adviser reassured her that, if she repented, God would forgive her. He also reminded her that our forefathers Abraham and Isaac both brought forth evildoers – Ishmael and Esau. But the woman wouldn’t allow herself to be consoled.

“My children will beat Jews!” she cried out in desperation. “I’ll never have any peace! Not in this world and not in the world to come!”

***

Once, the door opened and coming to see the religious adviser was an old man in a black fedora, an overcoat with silk lapels, striped pants, and a briefcase in his hand. The man had a thin gray goatee. He looked like an enlightened Jew who was no longer religious. The religious adviser asked the man to sit down.

“What good news do you bring?” “Rabbi,” said the man, “I’m going to propose something to you, but please don’t be angry.” “Why should I be angry? Speak clearly.” “This is the story,” said the man. “I haven’t lived as one ought to live. I’ve been preoccupied with my passions, with the material world. I’ve committed many misdeeds. I realize now that I lost my life to folly, but it’s too late. What I would like is for you to sell me a piece of your world to come. I don’t, God forbid, want the whole thing, just one year of Torah study and keeping the commandments. I’ll pay well.” “Is this a joke?” asked the adviser. “It’s not a joke.”

It turned out that the man was going around trying to purchase the world to come. He showed the adviser letters from pious men and religious scholars who had sold him either a year in the world to come, or a month, or even a week – as much as they could spare. Every single one of them had written out how much of the world to come he was selling and for exactly what price.

It did no good for the religious adviser to argue that you couldn’t buy and sell the world to come, and that the man would be better off donating the money to the needy and repenting on his own behalf. The old man had neither time nor desire for penance. He wanted to buy someone else’s world to come. He had a letter with him from some rabbi which said, in black and white, that you can buy and sell the world to come. That it’s a valid transaction. He was very disappointed that the religious adviser didn’t want to sell him anything. He’d come here hoping for a real bargain.

Was this man crazy? No. He got right to the point. He was simply a believer who also believed in the power of commerce. He’d spent his entire life buying and selling merchandise. So why couldn’t he also buy up a bit of the world to come? There were enough Jews in Poland who had plenty of it coming. And a little more or a little less of the world to come made no difference.

And who knows? Maybe this man even bought some for resale. Maybe he wanted to make a profit too. In the noisy and crowded life of Polish Jews, almost anything was possible.

***

Once the door opened and an old couple walked into the room. They were both in their late sixties.

“What good news do you bring?” the religious adviser asked his usual question. “We want a divorce,” said the woman. “A divorce? Why? You’ve been married for so long.” “We’ve married off all our children by now, may they all be spared the evil eye,” said the woman. “And we’ve already raised our grandchildren, thank God.” “Who’s ever heard of a man and woman living together for so many years and divorcing in old age?” asked the religious adviser. “I’m doing this for his own good,” said the woman.

It turned out that the old couple had a servant. The man had come to like the servant a little, but since he was so old already, it didn’t even occur to him to think of such things. All kinds of things can pop into an old man’s mind! But at some point he blurted out to his wife that the servant was pretty, and that had he been a young man without a wife, he’d have married her. It was hard to understand why, but these words had a powerful effect on his wife. She immediately declared that she was ready to give him a divorce. As if this wasn’t enough, she started convincing the servant that she should accept the match. She praised her husband to the stars, told her how much money he had, talked about his kindness, his reputation, and so – to make a long story short – the old wife talked the servant’s ear off until she promised that if the old man got divorced, she’d marry him. The whole thing had been settled between the old couple. They were here for a divorce.

When the religious adviser heard this story, he began to shudder. He warned both the man and the woman that they were heading down a slippery slope. “What’s wrong with you?” he asked. “The whole thing was concocted by the Evil Inclination.” The religious adviser warned the husband that he’d live a bitter life with the servant. He predicted that the wife would die of longing for her husband and that they would, God forbid, cut both their lives short. The rabbi called in the rebbetzin to help make his point, and she warned the old couple in even stronger terms that they should not give into this madness. The rebbetzin even went to speak to the servant and asked her to leave the old couple alone. But it seemed that the madness had taken hold of all three. It was all decided. The old woman had even had a trousseau made for the servant and gave her some of her jewelry. The three of them spoke as if they’d been hypnotized. It was a kind of nervous condition that took away their ability to think.

Needless to say, the adviser refused to divorce the old couple. But there was another religious adviser in Warsaw who went through with the divorce. And yet another adviser married the old man and the servant. The couple lived not far from the religious adviser and neighbors told him what happened to them. As unbelievable as it was, the old woman had gone to the wedding. She was the first to wish the servant mazel tov and to toast her with brandy and honey cake. The whole thing left people in shock, laughing but also in dismay. Women damned the old man and the servant with every kind of curse. People said that there had never – in the whole history of Warsaw as a city – been such depravity.

Some time passed and people all but forgot about the couple. Then, all at once, the courtroom door opened and in walked the old woman. She fell straight into a tearful lament: “Rabbi, help me!” It turned out that the servant, whom she’d helped take her place, held a powerful grip on the old man. He’d promised to pay his wife a weekly pension, an alimony of sorts, but he soon stopped the payments. The old woman was supposed to get some of the furniture and some of the housewares, but the servant kept everything. “For heaven’s sake!” cried the woman. “Where were my eyes?! Help – someone save me!”

“We warned you!” said the religious adviser. “I was blind! A madness fell over me! A wild madness!”

The old woman fell back onto a small bench and wept.

The rebbetzin brought her a glass of tea and a piece of buttered bread. The old woman cried as she ate. The poor thing was hungry. She’d fallen victim to a form of insanity that was years later discussed by psychoanalysts. But what difference did it make? No one could help her. The old man, for whose sake she’d sacrificed herself, wouldn’t even come with her to the courtroom.

***

Ahead of Passover, Jews come to register khomets – leavened foods forbidden during the holiday – which is sold to an intermediary for the period of one week. Once, a large well-dressed man walked in, and said he wanted to register his khomets.

“What kind of khomets do you have?” asked the religious adviser. “I have animals, which eat khomets.” “Animals? You obviously mean horses who eat oats?” said the adviser. “Not horses, animals.” “What kinds of animals?” “Lions, tigers, elephants, deer, monkeys.”

The adviser first thought the man was crazy. But he was completely sane. He owned a circus that traveled around Russia. It’s true that lions and tigers eat meat and not khomets, but a zoo is, in general, an institution that’s full of khomets that needs to be sold for Passover. Among the noodle boards and pots that the religious adviser sold to non-Jews every year, there were lions, tigers, elephants, a crocodile, and all types of snakes. These were the kinds of strange things that went on in the court. It’s hard to imagine how the adviser, a frail Jewish man, tried to sell – alongside the khomets – such wild and dangerous animals.

***

Once, a pale woman, with a large wig on her head, walked into the courtroom. She was carrying a basket with two dead geese with their heads cut off.

“Rabbi,” she said, “I have a frightful question to ask.” “What’s the frightful question?” “I had two geese. The geese were slaughtered. I cut off their heads. But they’re still shrieking.” “What do you mean, the geese are still shrieking?” asked the adviser. “Dead geese don’t shriek.” “Just look, Rabbi.”

The woman took one of the geese out and laid it on the table. Then she took out the other goose and threw it onto the first. There was a loud shriek – a goose’s honking cry.

“Did you hear it, Rabbi? Woe is me!” she cried. “Woe is me!! Everyone at home is scared to death. The children are crying and wailing.”

The adviser himself cried out. He told the woman to throw one goose onto the other again – and again he heard it shriek.

“It can’t be anything but a dybbuk,” called out an old man who was present. “How’s that? Why would a dybbuk possess a couple of geese?”

The adviser took out a religious tract and started looking through it, but there was no ruling on dead geese that shriek.

Suddenly, the rebbetzin walked in, and when she heard what was happening, she grabbed the geese, and tore out their windpipes. Then she said, “Now try throwing one goose on top of the other again.”

The woman threw one onto the other, but now the geese were silent. The whole thing was explained. Throwing one goose on top of the other had led the windpipe to let out a sound. The reason was purely mechanical. The adviser ruled that the geese were completely kosher.

“I still wouldn’t use such geese,” said the old man. “You can use them,” said the religious adviser to the woman. “They’re kosher.”

Below, the street had grown dark. Scores of Jewish women and men, girls and boys, all eagerly waited to hear what ruling the rabbi would give. Many predicted that the geese would have to be wrapped in burial shrouds and given a funeral. Imagine that – geese who shriek after being slaughtered!

The woman left triumphant, holding the two geese by their necks. The other women laughed, talked, and cried out. The young men whistled.

The woman who’d sold her the geese had come along too. Her business had almost gone under. It was all she needed – a reputation for selling geese with dybbuks!

It’s hard to believe that these very stories, and many others like them, took place in the city of Warsaw – in the twentieth century. Warsaw had a great deal of superstitious, religious Jews. Together with the destruction of Warsaw, we have also lost many other treasures – legends, customs, all kinds of superstitions, fantasies, remedies, incantations. On these religious Warsaw streets lived our greatest inheritance, left to us by our medieval ghettos.

Translator's Note

For reader's of Isaac Bashevis Singer, the themes and stories of this 1944 article will immediately recall the collection he later published in Yiddish as Mayn tatn's beys-din shtub (1956) and in English as In My Father's Court (1966). In his later treatment of this material, Singer distinguished between the term "father" when he referred to his father, and "rabbi" when characters addressed him. But in this earlier version, where he doesn't identify himself as the rabbi’s son, he creates this distinction by using the term מורה-הוראה (moyreroe) as narrator, while the characters call him rabbi. The term, which reads rather naturally in Yiddish, is difficult to translate naturally into the English, especially as a more literal translation would be "expert" or "guide" or "authority" in religious questions. I also tend to follow Singer's approach to translating his work, which glosses meanings of Yiddish words into the text rather than using endnotes. With this in mind, I decided on the term "religious adviser" or simply "adviser." My main translation dilemma was whether, for the sake of readability, to erase the distinction altogether and change all instances of "adviser" to "rabbi." In the end, I decided to keep the distinction, convinced that "adviser" is just natural enough in English to keep the reader focused on what counts most: the stories themselves.

Commentary

Isaac Bashevis Singer, “Religious Questions, Rulings, Divorces, and Weddings from a Rabbinical Court in Poland,” 1944. Commentary by Jan Schwarz

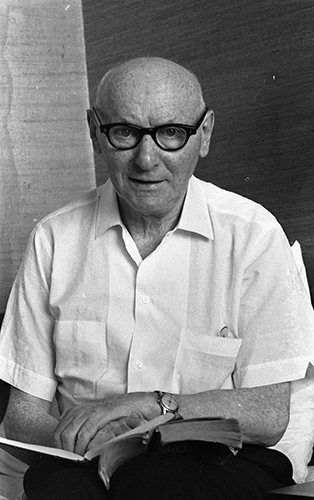

After emigrating to the United States in May 1935 from Poland, Yitskhok Bashevis (later known as Isaac Bashevis Singer in English) began working as a freelancer at the Forverts where he became a staff writer in 1942. Forverts, the Jewish Daily Forward, was the main Yiddish daily in the US. An important segment of the newspaper was devoted to fiction, criticism, and life-writing by leading Yiddish writers such as Scholem Asch and I. J. Singer.

Starting in 1939, Bashevis used the pseudonym Yitskhok Varshavsky (Isaac from Warsaw) for his weekly feuilletons in the Forverts. Varshavsky’s feuilletons during the war addressed some of the same topics that also informed Bashevis’ literary work: dybbuks and split Personalities; polygamy (‘filvayberi’); family life; the war; Jewish Poland, past and present; Yiddish names; and Yiddish literature.

Read Full

On August 13, 1944, a feuilleton by Varshavsky, “Shayles, din-toyres, getn un khasenes, vos flegen forkumen in a beys-din shtub in poyln” (“Ritual Questions, Lawsuits before a Rabbi, Divorces and Marriages which Used to Take Place in a Rabbinical Court in Poland”) appeared in the second section of the Forverts’s Sunday edition. Its stories about the shrieking goose and the divorce of the old married couple later appeared in expanded versions in Varshavsky’s series about his father’s rabbinical court in the Forverts in 1955 and in the book In mayn tatns bezdn shtub (In My Father’s Court, 1956).

The feuilleton belonged to the series “Jewish Poland, Past and Present.” Unlike In My Father’s Court, which is narrated from the perspective of Bashevis as the child of a devout father and sceptical mother, the feuilleton only hints at its autobiographical origins. Similar to the book, it consists of ‘tsikave geshikhtes’ (spicy stories) about the transgressive behavior of common Jewish folks. In a highly entertaining manner, the feuilleton depicts the meshugas (craziness) of the lowest strata of Warsaw Jewry “which the psycho-analysts first started to explore years later.” The feuilleton is an early example of the literary trends of commemoration of ‘a world that is no more’ that dominated post-war Yiddish literature.

1943 was the annus mirabilis in Bashevis literary career and the year he became an American citizen. His first American Yiddish book, Sotn in goray un andere dertseylungen (Satan in Goray and Other Stories) appeared under the imprint Matones Farlag in New York. It included his 1935 debut novel and newly written monologues in the series “Gedenkbukh fun der yeytser-hore” (“The Memorial Book of the Evil Inclination”).

In February 1944, his older brother, the Yiddish writer I. J. Singer (1893-1944), suddenly died of a heart attack at the age of fifty. Later that year, Bashevis received the devastating news that his mother and younger brother Moyshe who fled Warsaw after the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 had perished in a Soviet labor camp. Since 1923, I. J. Singer had worked for the Forverts, where he published feuilletons under his own and his wife’s name, Genia Kuper, and serialized acclaimed novels such as Yoshe Kalb (1932) and The Brothers Ashkenazi (1936). It was thanks to I. J. Singer, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1934, that Bashevis received the needed travel documents to travel to the U.S. and employment as a freelancer at the Forverts.

Whether writing as Varshavsky or under other pseudonyms, Bashevis was a remarkably prolific feuilleton writer. In 1944, Bashevis introduced another pseudonym, D. Segal, who wrote lighter pieces about human interest stories and Jewish Poland, such as “Many people like to gossip about their best friends” (July 19, 1944) and “Simkhes toyre in Eastern Europe” (Oct.10, 1944). As a result, Bashevis’ output as a feuilleton writer in Forverts increased more than twofold, from an average of 50 pieces each year between 1939-1943 to 107 in 1944 and 127 in 1945. As the ongoing destruction of Jewish Poland was regularly featured in the Forverts’ news and op-ed pages, Bashevis doubled his output in the Forverts to a level that would continue in the post-war period.

The feuilleton enabled Bashevis to address a variety of topics some of which he would recycle in his serialized novels and life-writing in the newspaper. It is my contention that Bashevis responded to the personal and collective catastrophe of 1944 by taking on the mantle of his older brother as journalist and novelist at the Forverts. This is also indicated by the more than twofold increase of his feuilletons in 1944. It made him an invaluable staff writer who worked overtime at the newspaper. The Forverts editor Hillel Rogoff praised him: “We, on the editorial board, cannot stop marveling about Bashevis’ prolific output. He produces more than two other writers who work full time at the newspaper” (Der gayst fun forverts, 1953, p.229) In November 1945, Bashevis began the weekly serialization of his family chronicle The Family Moshkat in the Forverts. Bashevis dedicated the novel to I. J. Singer, “his spiritual father and master,” when it was published in Yiddish and English translation in 1950.