Explore Feuilletons

The Incursion of Journalists into Posterity

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Keywords

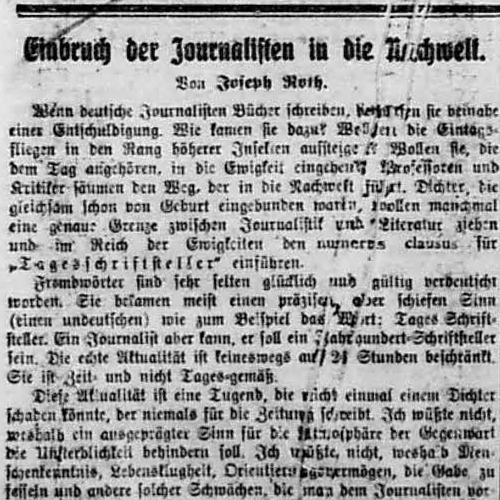

Original Text

Translation

Joseph Roth, “The Incursion of Journalists into Posterity,” 1925. Translated by Louis Kaplan

When German journalists write books, they almost need an excuse. How did they come to write books? Do the mayflies, who live but a day, want to climb into the ranks of the higher insects? Do they, who belong to the day, want to enter eternity? Professors and critics line the path that leads to posterity. Poets [Dichter] anointed at birth often want to draw a precise border between journalism and literature and introduce a numerus clausus for “daily authors” [Tagesschriftsteller] in the empire of posterity.

Germanification of foreign words has very seldom been felicitous or valid. The words have most often taken on a precise but skewed sense (an un-German sense), like for instance the word: jour-nalist [Tagesschriftsteller]. A journalist, however, can be—should be—an author of the century. Real timeliness is in no way limited to 24 hours. It is time-ly and not daily.

Read Full

Timeliness is a virtue that couldn’t even harm a poet who never writes for the newspaper. I have no idea why a fine-tuned sense for the atmosphere of the present should hinder immortality. I have no idea why knowledge of humans, the wisdom of life, the capacity for orientation, the gift of pinning things down, and other weaknesses that journalists stand accused of could damage genius. The real genius even delights in these errors. The genius is not turned away from the world, but turned towards it. Genius is not distant from the current living moment but near to it. It conquers the millenium because it masters the century. The misfortune of being misunderstood and misrecognized is not the trademark but an accident of the genius, which shares this pain in fact with average-talent journalists. Good craftsmen also go misrecognized from generation to generation.

Therefore—and although I, too, am a journalist—I don’t harbor any mistrust against books by authors who write for newspapers. Much poetry [Dichtung] has already run through the rotating machines of a newspaper and eternal truths have elevated the value of the paper whose destiny it is to end up in hushed and far-off corners.

The newspaper has to thank Alfred Polgar and Egon Erwin Kisch much more than can be paid with honoraria. What Polgar, following his own instinct, wrote “on the margins” of the time was, by the dictate of necessity, printed below the line. The tempo of Kisch’s “mad dash through time” does not define the transient nature of Polgar’s observations, and though his statements last only momentarily, they can be more eternal than the tedium of so-called “tranquility.” …

Kisch offers in his Mad Dash through Time (Hetzjagd durch die Zeit, Erich Reiß Verlag, 1926) not only a continuation of his Raging Reporter (Der rasende Reporter, 1925) as it could seem. The title is journalistic, belonging most properly above a newspaper essay. But the essays collected here, the reportage, novellas, journal entries, are the stuff of 26 novels—not that they need a treatment from a novel author.

They have already found their destiny. Reportage doesn’t need to be elevated to the rank of an “art genre.” It has its own artistic form precisely because it reports “only facts.” What Kisch communicates is the reality of a sensational rank. How much “art” is needed to make naked reality into an artistic truth? In a novella (“The Dead Dog and the Living Jew”), the author demonstrates his purely poetic ability, the craft of poetry. In the rest of the volume he uses it to lend actual experiences formal validity. Polgar once wrote about Kisch:

Today on proud steeds, Tomorrow: Garamond bold interleaved

Speed is a virtue of a good journalist. But sedation is far from a proof of the authenticity of the poet, if he scoffs at tempo and is scorned by tempo in turn.

Alfred Polgar’s book is called On the Margins (An den Rand geschrieben, Rowohlt, 1926). The modest title is a feather in the cap of the ironic author and will honor the buyer. Deep truths are written on the margins.

Polgar writes little stories without fable and observations without summary. He needs no actual “content,” because every one of his masterly articulated words is full of content. No occasion is too small for him. Precisely on small occasions is where he shows mastery. He polishes the daily so long that it becomes uncommon. What is he then to do with the uncommon? It’s no match for him. What is he to do with the “exciting events”? Every one of his sentences contains sensational events of language. His form is so subtle that no rough stuff, no palpable plot can entrust itself to that form. Sensational stories handle the poet with caution and avoid getting too close. They fear him. He could mock them and—woe is they!—they would no longer be sensational. His form bribes the truth. When he lets a heavy tragedy end in a joke one doesn’t even realize that the joke was random and the tragedy heavy. When he writes about something, it was him who made it “something.” There is nowhere another observer (working in German) who so resembles a Form-Giver, who so surpasses hundreds of other givers of form.

Commentary

Joseph Roth, “The Incursion of Journalists into Posterity,” 1925. Commentary by Matthew Handelman

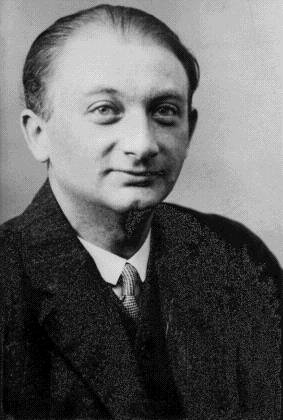

“The Incursion of Journalists into Posterity” appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung in December 1925 and is one of hundreds of feuilletons that the journalist and novelist Joseph Roth (1894 – 1939) published at the paper between 1923 and 1933. This text is a book review that, at least ostensibly, discusses publications by Roth’s fellow German/Austrian-Jewish journalists, Alfred Polgar and Egon Erwin Kisch. Polgar’s On the Margins and Kisch’s Mad Dash through Time, both of which appeared in 1926, were collections of reportage, essays, short fiction, and feuilletons. Roth’s text is thus also a feuilleton about journalism and journalists and their worthiness to be considered, respectively, literary texts and the authors thereof.

Read Full

During the Weimar Republic, the Frankfurter Zeitung and its feuilleton enjoyed a reputation as a prestigious cultural institution. The newspaper was founded by the Jewish banker and politician Leopold Sonnemann, in the aftermath of the 1848 revolution, and maintained a strong democratic and liberal political orientation up to the early 1930s. Run until the National Socialist takeover by Sonnemann’s grandson, Heinrich Simon, the Frankfurter Zeitung sat at the vanishing point of Jewish assimilation in Germany—an international newspaper for a general bourgeois readership that published numerous prominent Jewish journalists (like Roth, Siegfried Kracauer, and Walter Benjamin) and was also derided as “Jewish” by antisemites. Roth published reviews, including the text presented here, and travel reports for the paper, working as its Paris correspondent from 1925 to 1926 and later as a traveling correspondent from Russia, Italy, and Poland.

This text telescopes a long and persistent debate surrounding the cultural status of the feuilleton in German letters and beyond. Does the feuilleton measure up to the tradition of “high” literature from Goethe and Schiller to Thomas Mann? This debate, along with the question of the cultural assignment of the modern writer, appeared in various forms in Weimar-era literary publications, such as Die Weltbühne, Die Neue Rundschau, and Das Tage-Buch. Here, Roth frames the debate temporally: “daily writers” (playing on the German Tagesschriftsteller and French, jour-nalist) write in newspapers for the present moment, while poets (Dichter) and the authors of books are destined for eternity. Roth’s text dovetails on the forward to Polgar’s On the Margins, which defends the concise “small forms” of feuilletons, essays, and reportage against the oft laborious, “lingering description and observation” of “long literature.” For Roth, both Kisch and Polgar exemplify the legitimacy of journalism—with its “knowledge of humans, the wisdom of life, the capacity for orientation, [and] the gift of pinning things down”—appearing in book form. The timeliness of journalism, Roth contends, is not restricted to its daily appearance.

“The Incursion of Journalists into Posterity” also demonstrates Roth’s signature wit, which many also associated with the feuilleton as form. Take, for example, the text’s metaphor of “mayflies” (Eintagsfliege, literally one-day flies) for journalists and “higher insects” for poets and authors of books. This wit often accompanied Roth’s defense of the feuilleton, as in a 1926 letter to Benno Reifenberg, his editor at the Frankfurter Zeitung. “The feuilleton is just as important to the paper as its politics—and to the reader it’s even more important,” he writes. “The modern newspaper needs a reporter more than it needs a leader writer. I am not an encore, not a pudding, I am the main dish.” It was this confluence of newspaper and book, timeliness and eternity, news and the subjectivism of style, Jewish authors and mainstream German society that defined the feuilleton during the Weimar Republic.